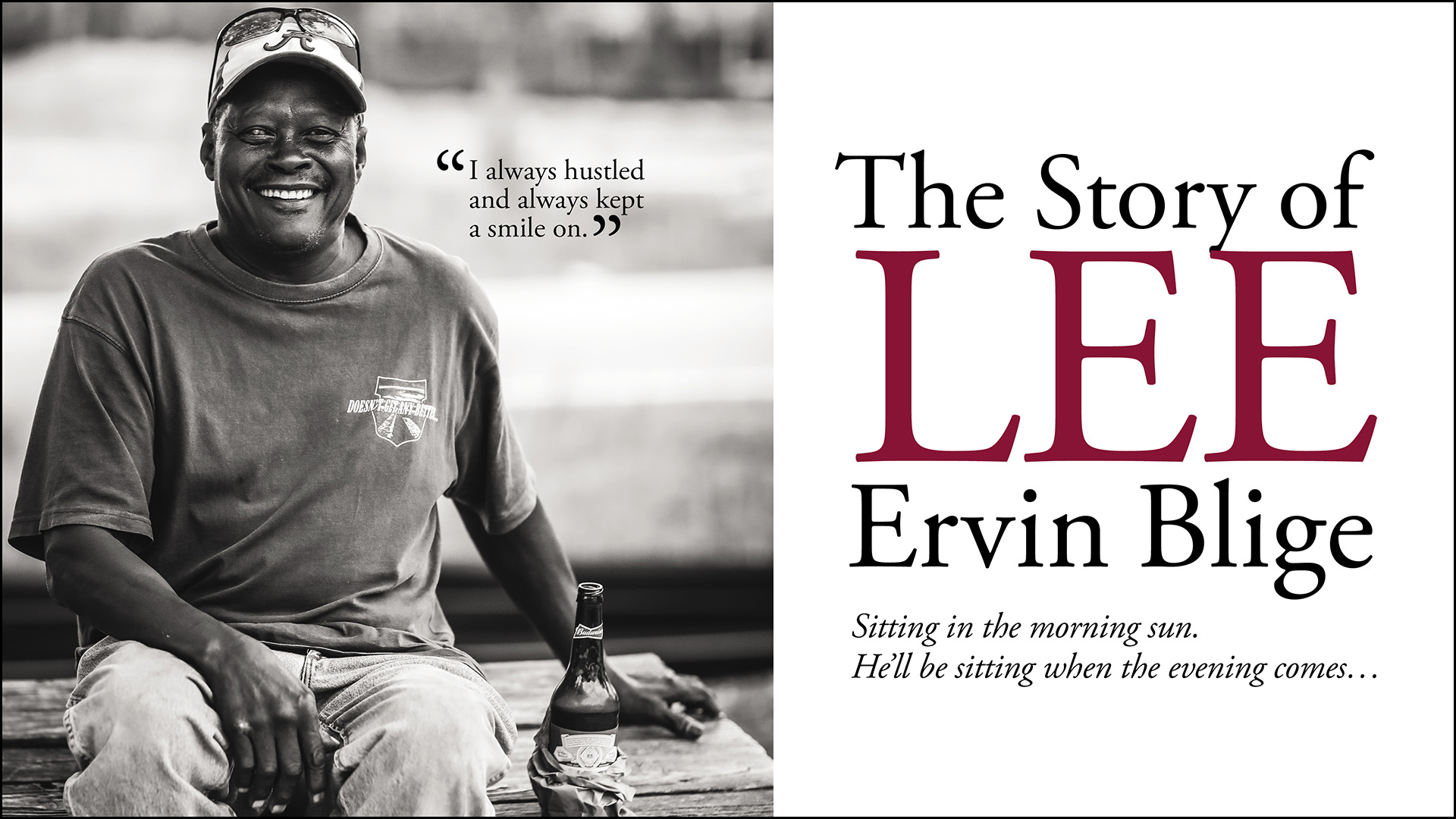

The Story of Lee Ervin Blige

WORDS BY Julie Osteen Seckinger PHOTOS BY Morris & Co. Photography

Sitting in the morning sun. He’ll be sitting when the evening comes…

Lee Ervin Blige (or Lee Irvin or Lee Irving as some call him, having mistakenly morphed his middle name into a similar last name). Perched on the picnic table outside the Zip-N (the corner store at Spur 144, now Enmarket), he is a wise ol’ hawk. You have probably seen him. But if not, make no mistake, he has probably seen you. He sees everything and everybody. He sits ready with a smile and wave of good morning or good evening, his red hat shooting up in greeting like a flare, and ready with the news—he reads the entire paper every morning before his 87-year-old mother takes him to the Zip-N where she plays Cash 3 before heading to the

Senior Citizens center. Sometimes he sits alone, contemplatively, but usually Lee holds court on the picnic bench with representatives from all genders, generations and races; a menagerie that at any given time may consist of the mail lady, a business leader, parents meeting for carpools with ballerinas and football players in tow, a member of his vast family, an old Richmond Hill railroad guy and a new guy from Ohio, a retired principal and a teenager. He can converse about just about anything, from international affairs to local marital affairs, and listens in a way few have mastered or even take the time to attempt.

The Blige’s are a respected family with roots going down in Richmond Hill soil to the 1800s. Lee grew up cutting wood to provide heat for the house and fuel for the stove, picking blueberries and string beans at The Ford Plantation, raising hogs and growing sugar cane. Some afternoons, his mother, aunts, cousins, and he would hold hands and walk Martin Trail through the woods of what is now Buckhead to the water to fish, cast for shrimp, and hand-line for crab. He got behind at Richmond Hill Elementary School, in the fourth and fifth grades. His friends passed him by. As punishment, his father allowed no summer activities except to work the field and cut wood. He decided to devote himself to making better grades, and with the help of the principal and teachers, he succeeded and went on to play basketball and run track in high school. The principal, Roger Jesup, didn’t want Lee working out on the water, where there were too many temptations to get in trouble. He got him into a youth skills program where he swept classrooms and did other jobs after school. He also taught him all about plants and how to grow and sell them. “I always hustled and always kept a smile on.” Lee remembers. “I bought my first land in the 11th grade, two and a half acres. I married my high school sweetheart, Rosa Houston. She was second runner-up Miss Richmond Hill. Our first date was to the fair.”

Lee and Rosa took a room in a boarding house and jobs in Savannah to save up money until they bought a house in Piercefield Forrest. “We were the first black family in Piercefield,” Lee recalls. “I had a drive to have: to have things, a house that doesn’t leak and you don’t have to put a bucket under leaks when it rains to catch the water, heat that doesn’t require cutting wood, a motorcycle.” He took a job at Reliance Universal, worked his way up, and transferred to Highpoint, North Carolina where he worked in research and development and later in sales and service. Then in a tragic turn of events, Rosa lost a battle with ovarian cancer, and Lee’s father lost his leg to diabetic complications and then later his life. “I took a nose-dive,” Lee says. The drive to have was replaced with drive to be. “I wanted to be back in the environment I grew up in and to give myself back to the environment where I grew up; to be surrounded by people, meeting new people and not being isolated, passing on what I know and can do—flowers, gardening, basketball—and teaching youth about real life.” And the rumor is he has taught half of Richmond Hill how to play basketball, including the Richmond Hill High School basketball coach Bill Henderson.

This started the meet and greet chapter of Lee’s life. His motto is: you have to keep moving. “Even when you feel bad, you gotta keep moving. It may be gloomy, cloudy, rainy, thundering, miserable, but another day is on the other side, with sunshine. I wanted to go on and meet people and keep them happy. It wasn’t having things that made me happy. I decided to earn what I could earn and make do. And help any way I could.” Hanging out at the Zip-N and around town, he became the unofficial Mayor of 144, meeting and greeting his constituents, remembering every child’s name and milestone in life in a way that would make any true politician envious. And soon, people began taking him into their homes and lives. On Christmas and other special occasions, like Santa, he checks off his list, leaving gifts of well wishes in his distinctive voice and manner. It’s unclear what made people trust him—his genuinely kind soul, broad smile and deep laugh, humbleness, intellect, wit—but they trusted him, and not only with cultivating their gardens, but with cultivating their children’s lives.

There is a consensus that his smile is one of Lee’s greatest assets, and Lee himself says a smile will take you a long way in life.

Lee has worked alongside Jimmy and Donna Norris family for about 20 years. For them and countless others, a day with Lee consists of some work, some play, a lot of talk, usually a mishap (which frequently involves a fire or explosion), and memories. Although proper compensation is always made (including a car once which became the Cavalier Lounge), it’s more like Lee is doing a favor and visiting than doing odd jobs—like having a friend or brother come over to help with a project and buying him some beer as a thank you (there’s no need to sugar coat it, we all knew there would be beer in this story, like it or not). And much like a friend or brother, the time spent working together brought them closer together. Donna Jones says, “I used to pick Lee up at 9am, go to the Keller Mall and get him his bounty, and spend the day making the yard look good. We would have a good time bantering back and forth telling tales. I called Mr. Lee the “mouth of the south.” But you could bank on what he said. He had the skinny on what was happening in the Hill. He even told me that my son had bought an engagement ring and was going to propose. And he was right.”

Lee is like a wellspring that overflows knowledge, talents, insights, traditions of old Richmond Hill and respect for new. It’s the passing down of this that makes him the happiest. Donna Jones says, “When I had a child to ‘disappoint me,’ the punishment was to put me in a new flower bed. Lee would always help and at the same time give his talks about doing right. He has been many a kid’s other consciousness.”

One of those kids was Frank Henderson. Frank lost his father, Dee (Devaul) Henderson, when he was just 13 years old. After that, Sundays were spent with the Murphy and Coleman families. Lee and Ricky cooked. Some of the Bliges would come and eat as well. Frank says, “Lee looked out for me and took me under his wing. He worked in the heat all day and still had time to teach me how to shrimp, fish, and drive. He played basketball day after day with my brother, Bill, after working all day. Lee is like your crazy uncle. You don’t ask your dad everything, but there are some things a boy needs to know. Lee is not scared to share it and tell you what’s going on and what to expect. He had a profound impact on my life. I learned so much from him about life, about work, and how to treat other people in a social aspect—it doesn’t matter where you come from, what you look like, who your family is. Lee can converse with anyone. His parents instilled values, and he was polished by those around him.”

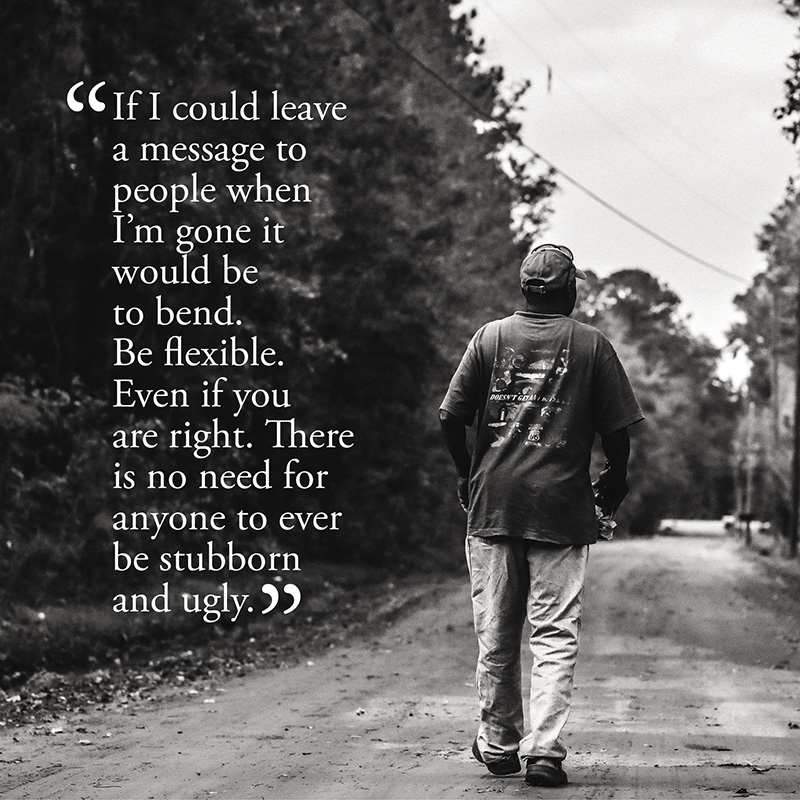

Growing up, Lee went with his family to Bryan Neck Baptist Church where he was baptized at an early age. He finds the services too long for him to sit through these days. “We make everything so long,” he says. “Our funerals are a week long. Everybody eats and drinks and tells stories for a week. And sometimes too much eating, and drinking, and storytelling leads to trouble. If I could leave a message to people when I’m gone it would be to bend. Be flexible. Even if you are right. There is no need for anyone to ever be stubborn and ugly.” Donna Norris says she wishes Lee had mentored one of his family members to step in after he is gone so there would be another Lee Ervin for the next generation, but Lee is one in a million.

A sense of calmness and consistency of life is measured by his presence each day. As predictable as the tides, you know what you are getting with Lee. But like tubing on the river, each ride has its own unique excitement and leaves you with a smile on your face. As one person stated on social media after the last hurricane evacuation, “Sun’s out! Zip-N is open. And Lee Ervin is sitting on the picnic table waving. The world is once again spinning in greased grooves.”.