Trapper Jack

Words By Christy Sherman | Photos Contributed By the Richmond Hill Historical Society

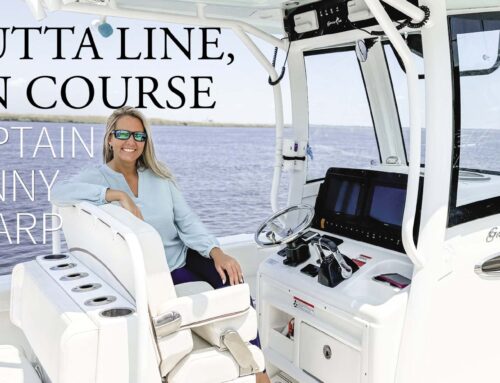

In March, Jack Douglas had eight stitches removed from his right hand. A piece of land was being filled in out on Fort Stewart. The alligators that lived there were not keen on moving. To prevent the alligators from being covered up and killed, Jack worked with the game warden to relocate them. No good deed goes unpunished, so they say. While attempting to corral one alligator, Jack fell, impaling his hand on a stick that was protruding from the mud. That earned him the eight stitches – after he finished hauling in the alligator.

Trapper Jack Douglas was born on September 25, 1945. He is up early because this 72 years young nuisance animal trapper has a lot to do today. There’s an eight-foot alligator out on Skidaway Island that is threatening to distract golfers during a weekend tournament. Another seven-footer has found a group of truckers over by the Circle K on Highway 21 who are willing to feed him regularly. That’s a liability the establishment just isn’t willing to take on.

“Some people don’t understand that these animals are never going to love you. They love that you have food. But when you decide you are going to walk out there without food, you are going to be the food,” Jack explains the mentality of the creature.

His interaction with wildlife started a young age. Jack grew up in Savannah. He attended Charles Ellis, then Richard Arnold, and graduated from Savannah High in 1964. “I didn’t get to graduate with my class though. They said my hair was too long and I just wasn’t going to cut it.”

Much like now, Jack spent most of his time outside and with his grandmother on Colonel’s Island. They would go squirrel hunting together and she taught him how to spot racoons in the dark. He remembers her as a prolific marsh hen hunter. “She did it different than everyone else. She would wait until low tide and paddle out with a .410 and a cane pole. Those marsh hens would come down to feed. She’d shoot them and hook them with that cane pool and drag them in, never getting the least bit wet. She’d do that until she had enough for dinner. She was an out of this world cook. She used a wood stove until the day she died. We got her a gas stove, but she never used it.”

A member of the Bonny Bridge Baptist Church in Port Wentworth, Jack is resolute in his relationship with wildlife that has spanned over four decades. “I fear the Lord. I don’t fear an animal. I respect them greatly, but I don’t fear them.”

That isn’t to say there hasn’t been some close calls.

Jack remembers one particular catch out on Skidaway Island. He had two young boys with him in the boat. “There were gators everywhere,” recalls Jack. He told the boys if they managed to get the “big one,” he was probably going to need some help. In hindsight, Jack figures he probably should have given some better training. He did end up with the big one. Once he caught the alligator in the snare, the problems started. The alligator went into a rage, pulling the rope and winding it out. In an effort to regain control, the rope ended up tied up around one boy’s arm, breaking the small bones in his wrist. Jack managed to free the boy and twisted up his own hand in the process. “Me and that gator were this close,” he says, motioning less than an arm’s length away, “and the only thing between us was this short side of this aluminum boat. The rope had caught my finger, but we finally got it loose. We lost that gator that night, but we got him two years later.”

Jack estimates that he is close to 10,000 alligator captures to date. Most of them come from the Savannah area— nearly two or three times the calls than the rural areas. “In those places, people don’t call, they just shoot them. It’s illegal, but that’s what they do.”

Most interactions between alligators in the wild and the public are regulated in Georgia. There are statues against feeding or baiting alligators. The hunting of alligators is a highly controlled process. To legally hunt an alligator in Georgia, a person can apply for one tag every four years via a lottery system. Hunters with a tag can choose to hunt on their own or call someone like Jack to be a guide.

n fact, there are only about 7 or 10 people in the entire state who can legally remove alligators measuring over four feet. The licensing is regulated by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, who instituted the agent trapper program in 1989. Jack was among the first applicants to attend the then three-day course that earned him one of the first licenses to capture larger nuisance alligators. He is currently the only licensed trapper of this kind in four counties, including Bryan.

Out of those 10,000 captures, Jack has only cracked the 13-foot mark once. 14-foot gators, he says, are “one in a million. It’s like those 200-pound deer down here, you hear about them, but it just isn’t so.”

He thinks highly of the skills from the alligator hunters on the popular show Swamp People, but he doesn’t think the show does them justice. “They are a lot better than they let them be on TV. I think the producers make them do that. The Gator Boys are pretty good too. But that Australian Outback show, that’s the real deal. That’s how it really goes.”

Going to Australia is a dream of his. He trained two young sisters from Skidaway Island. “Those girls could skin a gator in no time flat. And they were good at it, too. They were fast, and they would never put a hole in it.” One of the girls has moved to Australia and is working with crocodiles. He would love to visit her. However, Jack doesn’t see that happening. He has issues with his ears that make it near impossible for him to fly. It has been that way since his time in the National Guard.

There isn’t too much difference between alligators and crocodiles explains Jack. “Except a crocodile’s skin is prettier. They don’t fight. They live more peacefully. Alligators fight over everything. It leaves their skins scarred and beat up.” The scars have made an impact on the sale of the alligator skins.

Trapper Jack doesn’t spend all his time with alligators. In fact, a wild boar still stars in his favorite hunt story and coyotes are his favorite animal to work with.

“I had a guy from New York who called and wanted to go boar hunting. But, he didn’t want to just go boar hunting, he wanted to do it with a spear.” Once he had accomplished that, he told Jack he wanted to do it with a knife. Jack was more than happy to oblige him. “You’ll hear hunters talk about boar hunting with a knife. What they mean is that they have a bulldog drag the boar down by the ear and hold him while the hunter kills him. That’s not what he did.” Jack explains that instead, the dogs only boxed the boar in, then the man allowed the boar to charge him, face on. “He missed the first time and the boar gouged his hand. He got him the second time.” Jack loved those trips. New York came down every year until he died in a work-related accident.

The choice of the coyotes comes from the intelligence of the animal. “They are just so smart. Their noses are so keen. It’s like they have a built-in metal detector for the traps. If there is anything on them, a trace of human scent, the slightest bit of rust, anything, they will sniff it out. I’ve seen traps completely dug out and around, bait gone, trap intact, coyote gone. I use a deer carcass mostly. The scent is so strong, and the coyote gets so excited, he’ll mess up.”

Not looking to retire any time soon, Jack loves what he does.His license is for a lifetime. He can keep taking the calls as long as he is able to do the work. He is very capable of doing the work. He hopes that remains the case for a long time to come. Jack can’t imagine doing anything else. His relationship with the wildlife has enriched his life more than some might think.

In the early 70’s, Jack’s hog hunting had slowed down for the summer. He travelled up to North Carolina to take a job working on the pier until the weather cooled back down. While he was there, he also worked capturing wild hogs on the beach. A baby hog took to following him around. During one of their walks on the beach, the hog left Jack and ran up to a young woman laying out on a blanket. That was nearly 44 years ago. Jack and his wife Amy have been together ever since.