Sandy Footprints

Words By Julie Seckinger

Eleanor (Sandy) Torrey West is an artist, adventurer and award-winning author and conservationist. Undoubtedly, she is most known for her determined efforts in making Ossabaw Island the first Georgia Heritage Preserve in 1978, ensuring that those who follow her will walk along the same unspoiled, enchanted island.

For thousands of years, Native Americans lived among the 26,000 acres of marshes, sloughs and creeks, beaches and dunes, yaupons, oaks and palmettos, oysters and osprey that make up Ossabaw Island. It is believed that the island gets its name from the European interpretation of Asopa, the name of the Indian village that was once located there. Destroyed by the Spanish in 1570, shell middens are now the only visible trace of its existence.

Through the colonial and antebellum periods, Ossabaw passed through several owners and was used for timber, raising livestock and growing sea island cotton and indigo. A group of businessmen from Strachan Shipping bought the island for a hunting retreat in the early 1900s. These endeavors left their mark on the island. Though not in its original state, it is a remarkable example of an island in recovery. Without future impact, the process can be documented over the coming decades.

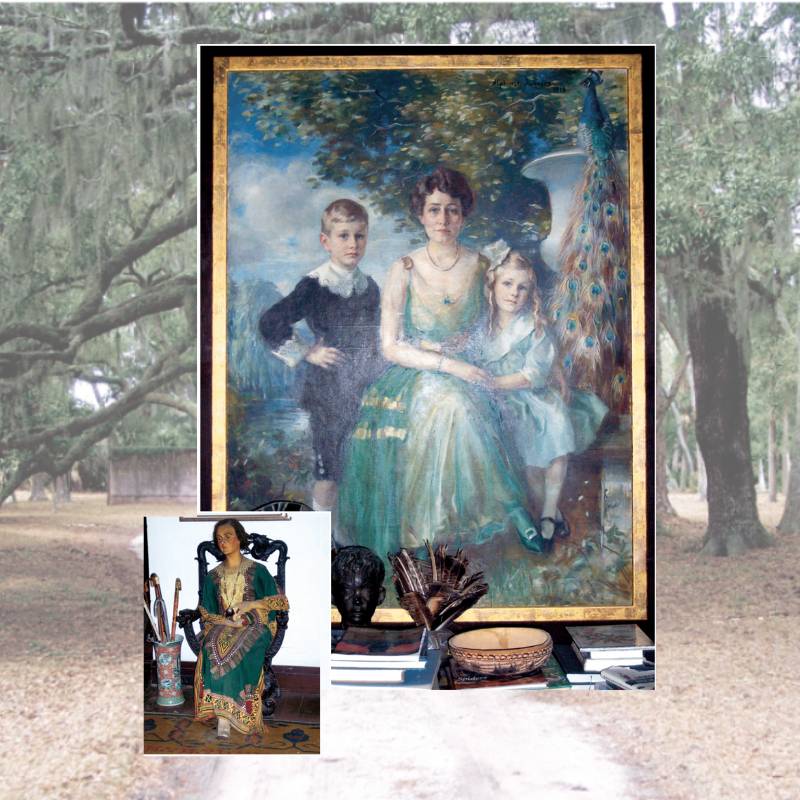

Sandy West, from Grosse Point, Michigan, was first introduced to the island in 1924. Everyone who could left Grosse Point during the frigid winter months. According to Mrs. West, the Torrey family didn’t like spending the season at resorts as most families did. They purchased an estate, Greenwich, on the Wilmington River in Savannah in 1917. Tragically, it burned. Nell Ford Torrey – granddaughter of John Baptiste Ford, a shipbuilder who later founded the Pittsburgh Glass Company and conducted the first successful plate glass pour in the United States – searched for a suitable new home for her family and was offered Ossabaw Island. “Mother wondered what one would do with an island. And it was twice the size of Bermuda,” Mrs. West remembers. “She offered them a ridiculous figure for it, $150,000, and they accepted.”

What would one do with an island, indeed? Taking inspiration from the island’s Spanish history, Dr. Henry Norton Torrey built a 20,000-square-foot Spanish Colonial Revival style villa with 15 bedrooms, 16 baths and magnificent gardens for his wife overlooking the Ossabaw Sound. Over the years, two small beach houses were constructed, which were both claimed by the sea. The remainder of the vast barrier isle was left in its gloriously wild existence.

It was a glamorous era when ladies and gentlemen dressed for each occasion and lived and entertained in style. The Torreys explored the coast on their yacht and visited friends on nearby islands, hosted grand picnics, barbecues and hunting parties. Mrs. West and her brother William had countless adventures with their friends, exploring the island on horseback or through the spartina-lined waterways by bateau. “It was a different time then; the world wasn’t falling apart. We didn’t have the concerns we do today,” Mrs. West muses. “I thought things would always be the same.”

In the 1950s, Mrs. West and her brother’s children inherited the island. “I had a much more educational approach to the island than my mother,” Mrs. West says with a smile. “She loved her gardens and flowers, especially azaleas. I took down the fences.” And she let the gardens and animals wander freely, even opening up her home. Roaming donkeys have scared more than a few dinner guests.

She also opened her home and island to the great minds of the world through ventures including the Ossabaw Island Project and Genesis Project, believing that the magic of the island and the conversing of people of mixed disciplines would create inspiration and new ideas. And it did. Mrs. West funded the projects, sometimes at the reported cost of $500,000 a year, for over a decade. Finally, it was financially unfeasible to carry on. She had to seek a suitable steward, one that would continue to share the essence of Ossabaw without changing it and without ever developing it further. After an eight-year search, a solution was found. The State of Georgia would purchase the island as the first Heritage Preserve and adhere to the family’s special stipulations on how it could be used, including that it never be developed and that a bridge never be built connecting it to the mainland. The island was appraised at $16 million; the state could only fund $8 million. So the family donated $4 million and it was matched by a donation from Robert Woodruff. Mrs. West retained a life estate to the main house and grounds.

Mrs. West graciously invited Robert and Kelli Anderson and me to lunch at her home on Ossabaw to discuss her incredible life thus far, what she sees for the future and her new book, written with her longtime friend Elizabeth Pool, God of the Hinge: Sojourns in Cloud Cuckoo Land.

A black pig with tusks greeted us immediately at the landing. “He probably just wanted to give you a kiss,” Mrs. West assures us. “He came by my window last night looking for one.” He is one of many Ossabaw Island pigs, descendants of Iberian swine brought over by the Spanish, which overpopulate the island and have been the subject of much study. An article on the superior flavor of their meat by Peter Kaminsky even appeared in the New York Times.

As we sat down in the great room beside a large window, we spotted a deer and an armadillo side-by-side on the front lawn. We amused ourselves with watching them for a while, waiting to see which would run off first or if they were enjoying each other’s company. Just as we were settling back into conversation, something caught my eye outside again. A herd of donkeys approached. Mrs. West was as delighted as we. Her face lit up and we stood watching from the window again. Knowing each by name, she introduced us. “Would you like to hear the story about the donkeys?” she asks as if offering a child a cookie, though not in a coaxing or condescending way. Her voice and smile are magnetic and a little mischievous.

Mrs. West explained that years ago she learned of a man who had imported a menagerie of animals, including Sicilian donkeys. He died, and the new owners had to get rid of the animals. Wanting to save the donkeys, she decided to buy four or five. She drove over and picked them up in a Volkswagen van. On the way home, she had to run a few errands and stopped by the post office. “I drew quite a crowd around the van,” she laughs. “Once I got them here, the donkeys bred rather quickly, and I had to do something to control them. So, I went to Roger (island manager) and asked him which he would prefer: to be castrated or sold to some jerk.” He chose being castrated. “I really didn’t want to castrate them; I wanted to find someone to give them all vasectomies.” This turned out to be a difficult task; no one local would do it. She found a group from Penn State that agreed to perform the operation on about 50 donkeys. “They showed up in their uniforms with all their shiny instruments and asked where the operating room was. I showed them the field. Roger and I helped. There were only three fatalities, all female. They died of shock.”

As she speaks, it’s evident that her spark of passion hasn’t waned over the years, though she laments, “It’s depressing to look at the world today and see what it should be, to see the ruinous attitudes, stupidity and fear — fear of the unknown. The only thing to save us is something new — new experiences and thinking. I’m not pessimistic; I’m realistic. It has to be now or it will be too late. That’s why I tried so hard to save the island. Ossabaw has become rare, but it is actually the real thing.

“People are so busy now doing nothing; it’s boring. They shuffle over their papers, digging themselves deeper and deeper. They have no time to think. And the noise, it’s everywhere. There is even music in maternity wards now. It drowns everything else out. One of the worst things is the internet. Not only does it ruin your eyes, you don’t get your feet wet. It’s all second-hand knowledge.

“With the Ossabaw Project, we had fabulous people here. They found time to be by themselves and do miraculous things. I didn’t torture them by asking where they were on their project; that would just put them right back in that world.” According to Mrs. West, not everyone embraced the project or the island. Some were afraid and left. But most were changed, inspired and enlightened. “Something about Ossabaw did that,” Mrs. West says. “No one takes the time to let new thoughts come in.”

Is there magic surrounding Ossabaw or is it simply the beauty and primeval state of the island that is powerful? Mrs. West believes that it could be both. She explained that there is a theory that a belt of energy runs under some places, ley lines, giving them a certain power. Ossabaw could have such an energy. Or, it could be that true magic is simply that which has yet to be discovered and Ossabaw provides the solitude and stirring to unlock the secrets.

In her book, published last year, Mrs. West and her friend Elizabeth Pool recount the tale of their 70 years of journeys, discoveries and revelations that were, as former President Jimmy Carter writes on the back cover, “heavily influenced and inspired by nature, mythology and imagination.” Included in the book is the story of how Mrs. West came to be called Sandy. I had for some reason incorrectly assumed it had something to do with the beach or island. Mrs. West explained that she had always been called “Sis.” When she became engaged to her first husband, whom everyone called Bud, she decided she needed a new name, not wanting to be known as “Bud and Sis.” But she didn’t want to go by Eleanor. During one of the adventures, Mrs. West, a blonde, and Mrs. Pool, a red-head, were dining when a drunk man approached their table and called them Rusty and Sandy. She has used the name ever since.

Mrs. West explained why she felt compelled to publish a book now, in her nineties. “We had to go through all the adventures and get to a stopping point. But there really is no end.”

So, what’s next? “Shutting up,” she says. “I’ve saved the island. Now I’m just going to shut up and see what appears.”