The Great Escape

of William and Ellen Craft

WORDS BY CHRISTY SHERMAN PHOTOS COURTESY OF GRANGER

SPRING 2022

On December 21, 1848, passengers scurried about on a railway platform in Macon, Georgia. A man approached the counter and purchased two train tickets to Savannah – one for himself and his servant. The man was dressed nicely in a suit and tie and a top hat, a symbol of fashion and the hat of choice for society gentlemen. However, it was clear that he had sustained injuries or had an ailment, as evidenced by the sling holding his right arm and the poultice, or medicated cloth, secured to his face by a white handkerchief under his chin tied at the top of his head. Despite not being able to write or speak very well because of these bandages, the man successfully secured the tickets. He proceeded to board one of the finest train carriages available to upper-class White people. The servant, a Black man, named William, boarded separately because the train cars were segregated based on race and economic and social status.

Just before the train departed the station, William spotted a familiar face on the platform from his window. Another man with whom he had worked for years was a fellow cabinet maker. William saw the man asking questions to the ticket seller and then looking into the different carriages, including the one occupied by his master. Nervously, he shrank down into his seat, hoping not to be seen by the man. Suddenly, a bell rang, and the train began to move before his car could be inspected, much to William’s relief.

Meanwhile, William wasn’t the only one experiencing a troubled start. In the other train car, his master saw a familiar face on board, Mr. Cray, a frequent guest of the plantation on which they lived. As a matter of fact, he had just dined there the night before. Hoping not to draw the attention of Mr. Cray, he turned toward the window. As Mr. Cray strolled the aisle, he proclaimed, “It is a very fine morning, sir,” to which he received no response. But, you see, had the master turned to answer him, Mr. Cray may have seen through his clever disguise. William’s “master” was his wife, an enslaved woman. Together, they had just taken the biggest risk of their lives.

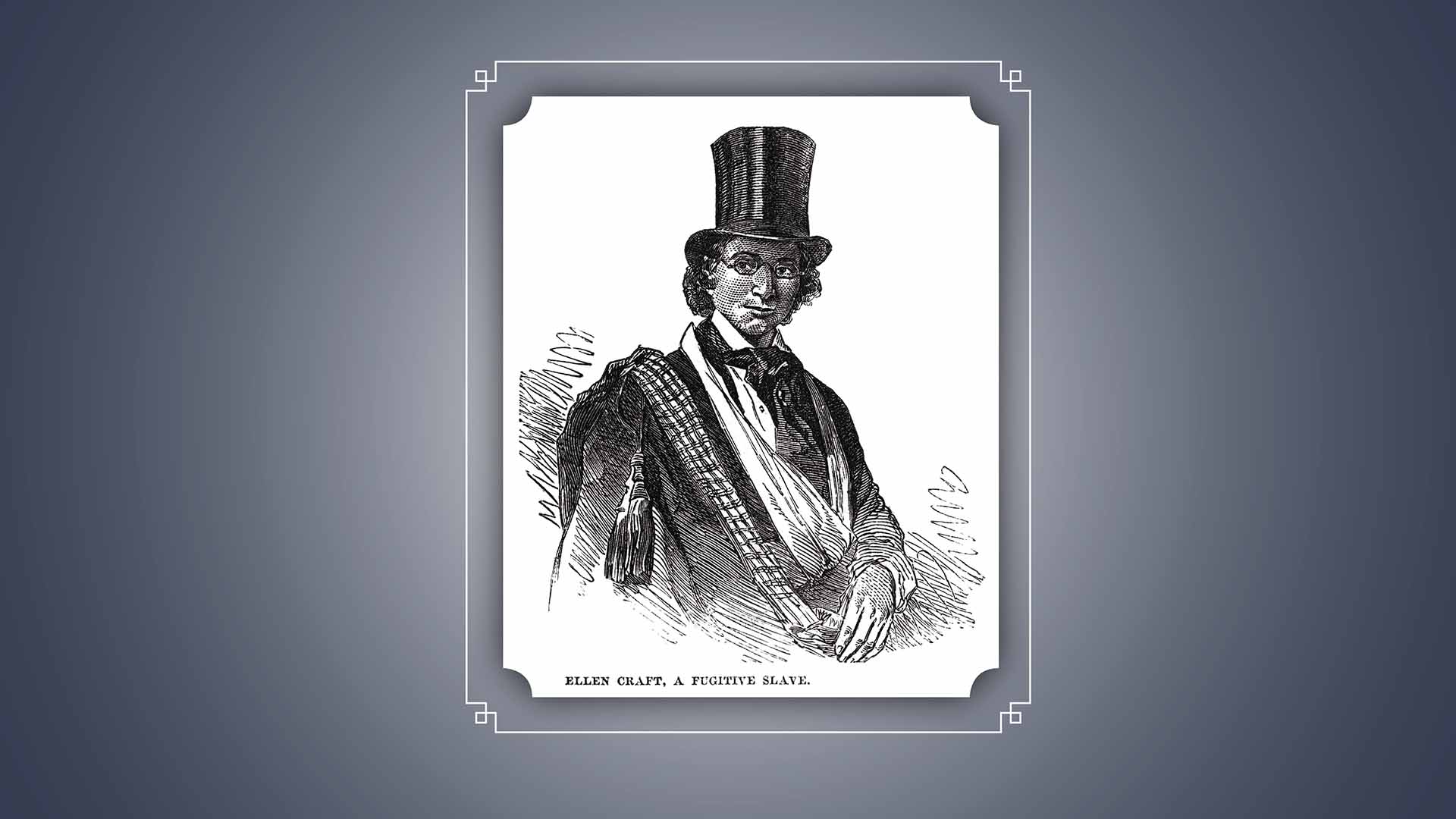

William and Ellen Craft had concocted their plan to escape slavery just four days earlier. Ellen, whose father was a white man and her mother of mixed race, had a very fair complexion. With a haircut, the proper clothing, spectacles, and a top hat, the couple believed she could pass as a white man traveling with a servant (it was not customary for a white woman to travel with a manservant). Moreover, since neither party could read or write, the arm sling would give her an excuse for not being able to provide a signature if asked, and the face bandage would help conceal her smooth and more feminine facial features.

These safeguards worked, for the most part, but not without more harrowing close calls. The couple arrived in Savannah and then continued through the Carolinas and Virginia. In Charleston, they were held at a checkpoint until their identity could be verified. Fortunately, another passenger they had met stepped in and vouched for them. During travel on trains and steamers, Ellen had to endure uncomfortable conversations with her “peers” about slavery and unsolicited advice about how she was spoiling William by telling him “thank you” and such. When presented with a document or reading material, she had to quickly put it away in fear of holding it upside down since she could not read. In Virginia, a woman thought she recognized William as her runaway slave, Ned, and demanded he come with her until she realized it was a case of mistaken identity. Their anxiety increased as they arrived in Baltimore, the last slave port. They had heard there were stringent rules about traveling with enslaved people since the next state, Pennsylvania, was a free state. Sure enough, an officer promptly approached William at the train station and interrogated him about where he was traveling. His master would have to satisfy the officer that he had a right to take him into Philadelphia. This drew the attention of a large number of other passengers who sympathized with Ellen as a legitimate “slaveholder and invalid gentleman” and voiced their opinion that the couple should not be detained. Finally, the train bell rang, and the flustered officer reluctantly let them go.

The next day, Christmas morning, the train reached the platform in Philadelphia, and William and Ellen were free.

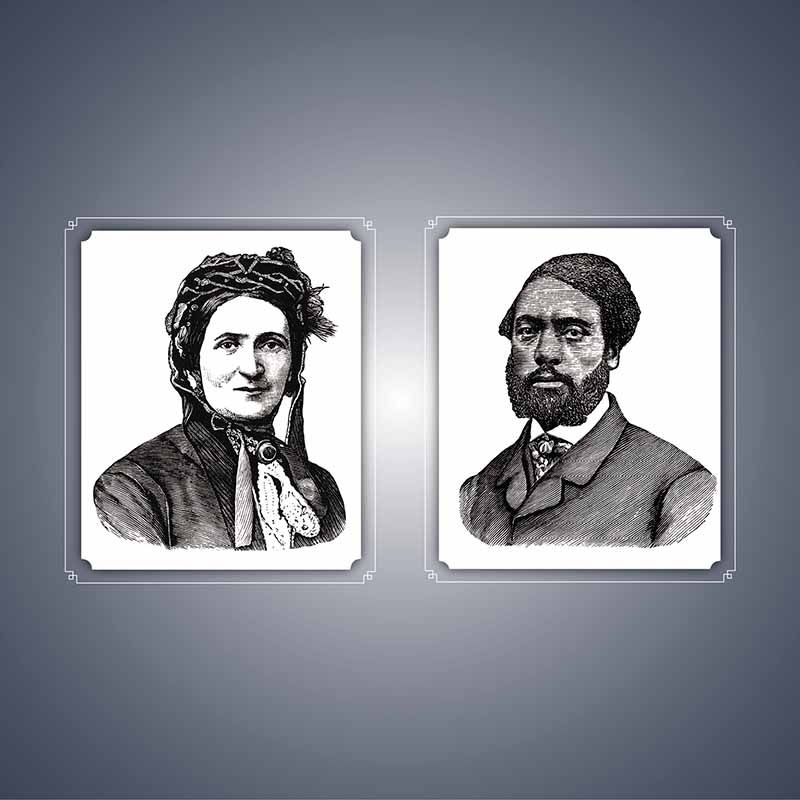

Upon arriving, William and Ellen were given assistance, food, and lodging by an underground abolitionist network that William had learned about on the train. They were advised to settle in Boston, and they moved a few weeks later. William resumed work as a cabinet maker and Ellen, a seamstress, skills they had both learned during slavery. On October 25, 1851, slave catchers obtained a warrant for William and Ellen’s arrest through the Fugitive Slave Act. A Boston Herald article announced the warrant and identified William Craft as “in the cabinet making business at 51 Cambridge Street.” The Crafts had the support of many abolitionists and friends in the community and avoided capture. Nevertheless, they decided to flee to England, where they remained for the next twenty years.

“It was not until we stepped upon the shore at Liverpool that we were free from every slavish fear. We raised our thankful hearts to heaven and could have knelt down like the Neapolitan exiles and kissed the soil for we felt that from slavery,” William would later write in his book, “Traveling a Thousand Miles for Freedom” in 1860.

While in England, the Crafts became active in the abolitionist movement and started a family. After the Civil War, in 1868, they returned to the United States and eventually back to Georgia with their children Charles, Alfred, and Ellen, while William Ivens and Brougham remained in England. In 1870, the Crafts purchased the former Woodville Plantation tract in Bryan County (south of Ways Station on the Darien-Savannah Stage Road, now Highway 17). With the help of friends from Boston, they established the Woodville Cooperative Farm School, modeled after the Ockham School in Surrey, England. William and Ellen spent most of their savings and took out a $2,500 mortgage to build the school and a chapel for the education of freed men, women, and children.

The Woodville School was successful until 1875, when George Appleton, the husband of Bryan County planter Richard J. Arnold’s granddaughter Luly, accused William of using charitable donations for personal purposes. William unsuccessfully sued for libel in 1876. With increasing debt and anti-Black violence, the Crafts moved to Charleston in 1890 to live with their daughter’s family. Ellen died in 1891; William died in 1900. At Ellen’s request, she was buried under her favorite tree on the Woodville Plantation. William was buried in Charleston.

This past February, the Richmond Hill Historical Society was awarded a $6,000 grant for a new display about the Crafts’s extraordinary escape story and contributions to Bryan County by Americana Corner. The founder of the organization, Tom Hand, said, “I am proud to help the Richmond Hill Historical Society tell the account of William and Ellen Craft through my Americana Corner Grant Program. The Crafts’ efforts to overcome adversity are inspirational. In my opinion, local organizations like the Richmond Hill Historical Society are critical in telling the Great American Story and need our continued support.”

In both America and England, some of the Crafts’ descendants are still active in researching and telling their family’s story. Julia-Ellen Craft Davis, a great-great granddaughter, has visited the Richmond Hill History Museum and Bryan County several times. Upon hearing the news of the grant, Ms. Davis replied, “It is important that Ellen and William Craft’s story will be shared with this exhibit for future generations in south Georgia and for travelers to the Richmond Hill History Museum,” said Julia-Ellen Craft Davis, descendant of the Crafts. “The public will learn that the Crafts informed others about slavery and how they assisted people of color in New England, Great Britain, Dahomey and eventually at great sacrifice they returned to their home in Georgia.”

For more information about the Crafts’ daring escape story, visit www.RichmondHillHistoricalSociety.com