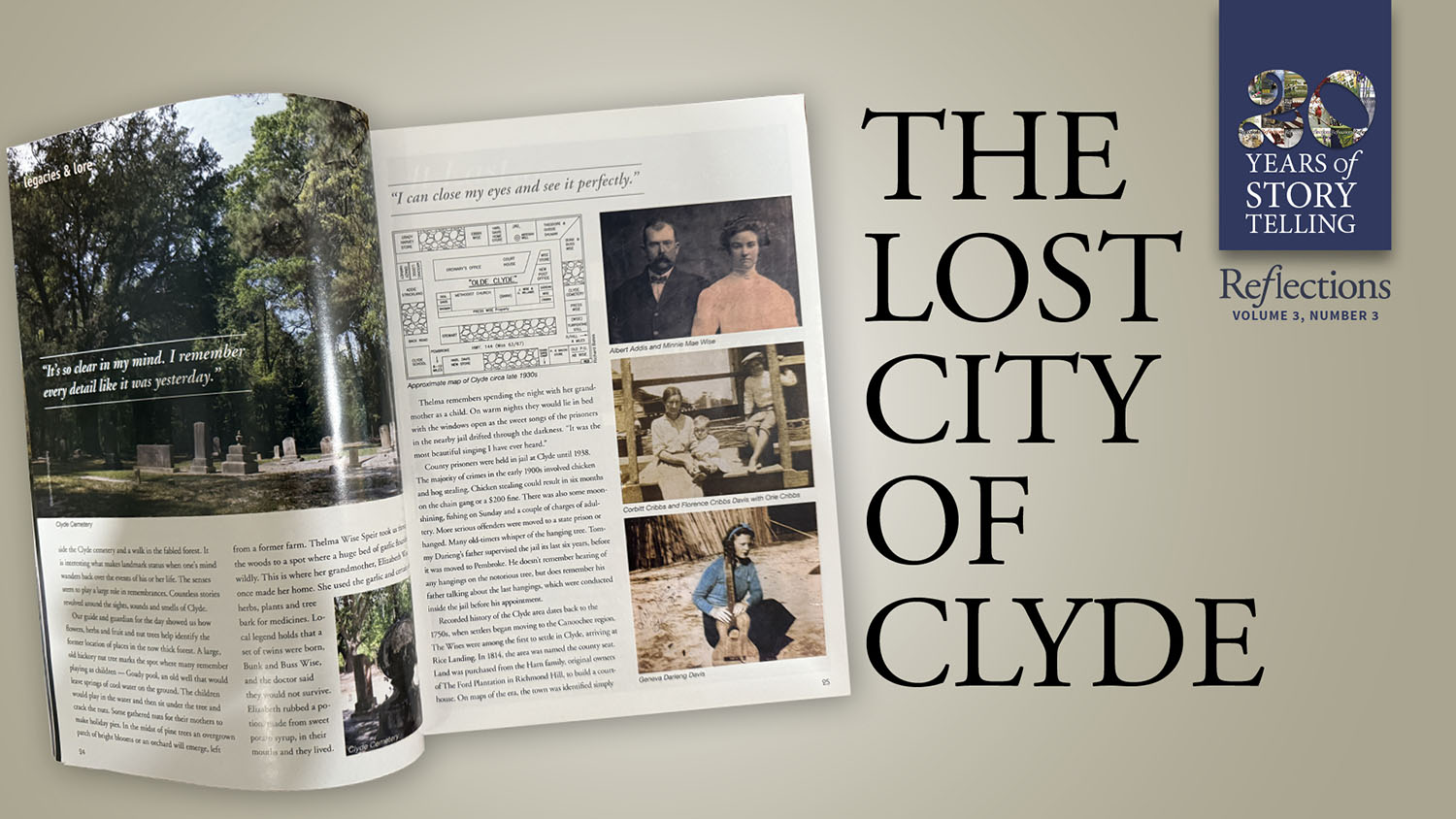

The Lost City of Clyde

Words By Julie Osteen Seckinger

“Are you ready?” says Ada Shaw Martin, her eyes fixed on us. “I’m going to give you a tour of Clyde.”

Clyde sits nine miles west of Richmond Hill, down a dirt road that runs through tidewater swamps and thick forests. We cross a wooden span over the Canoochee River.

“The people of Clyde used the water from the Canoochee to make the best coffee,” she says.

No one seems to be certain of the correct name of the bridge—Boles or Balls, maybe. As is the case with many local places, the pronunciation and proper name don’t always resemble each other.

As we continue on, she points out a cemetery that dates back to the early 1800s and a holy-rollers’ church that she was forbidden to enter. “That’s where the county buried two men,” she tells us. “No one ever knew who the men were. They just brought them here and buried them, with no marker or anything. Everyone was outraged, but it didn’t make a difference.”

An anecdote almost always follows as she notes each and every home along the way—mostly farms—in the settlements on the outskirts of the former county seat, which include Shakerag, Roding, and Shumantown. Here lived a lady who was the nicest person anyone would ever want to meet and sold equally nice moonshine. There, another who grew the prettiest poppies.

As we approach Clyde proper, we pass the turpentine still and Press Wise’s store. “My girlfriends and I would search the ground outside the store for pennies so we could buy candy. Later, we found out that some of the men would drop the coins for us.”

She points out three other general stores, the courthouse, post office, and jail. “That’s where I went to school—Clyde Consolidated School. First through seventh grades went to school here. After that, you went to school in Ways Station. John Darieng drove the school bus. After school, there were baseball games or kids played marbles in the street. We’d wrap a stick up in a blanket and make it our baby. We just played. The men would gather on the courthouse steps, and the women would visit on someone’s porch. Sometimes there were dances on the weekends.”

Next, she takes us to the Methodist church. The story goes that until 1886 there wasn’t a church in Clyde. One night, an earthquake struck Charleston and could be felt all the way to Clyde—it shook the lanterns off the tables and the chickens off their roosts. The next morning, the townspeople got together and started building the church.

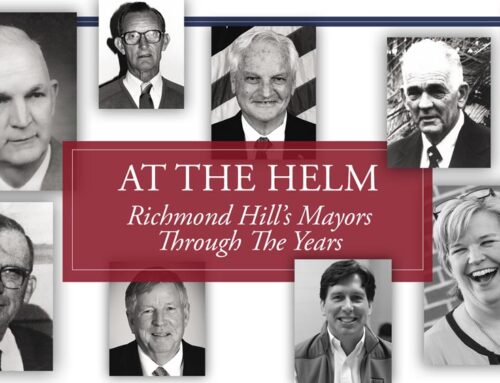

Ada looks up from her drawing to make sure we are following her. The tour is only on paper. Every home, every business—the courthouse, jail, post office, school, and even the sacred church—disappeared more than half a century ago.

“I can still picture it so vividly,” she says.

It will never be erased from Ada’s memory, nor from that of many others like her. Not a detail forgotten, and yet it only exists in their minds. The only traces of Clyde are the town’s well and cemetery—symbols of life and death.

We took a small group of people, each having a connection to the community’s past, for a picnic on the lawn outside the Clyde cemetery and a walk in the fabled forest. It is interesting what earns landmark status when one’s mind wanders back over the events of a lifetime. The senses seem to play a large role in remembrance. Countless stories revolve around the sights, sounds, and smells of Clyde.

Our guide and guardian for the day showed us how flowers, herbs, and fruit and nut trees help identify the former locations of places now hidden in the thick forest. A large, old hickory tree marks the spot where many remember playing as children—Goady Pool, an old well that would leave springs of cool water on the ground. The children would play in the water and then sit under the tree and crack the nuts. Some gathered nuts for their mothers to make holiday pies.

In the midst of pine trees, an overgrown patch of bright blooms or an orchard will emerge—left from a former farm. Thelma Wise Speir took us through the woods to a spot where a huge bed of garlic flourishes wildly. This is where her grandmother, Elizabeth Wise, once made her home. She used the garlic and certain other herbs, plants, and tree bark for medicines.

Local legend holds that a set of twins were born—Bunk and Buss Wise—and the doctor said they would not survive. Elizabeth rubbed a potion made from sweet potato syrup into their mouths, and they lived.

Thelma remembers spending the night with her grandmother as a child. On warm nights they would lie in bed with the windows open as the sweet songs of the prisoners in the nearby jail drifted through the darkness. “It was the most beautiful singing I have ever heard.”

County prisoners were held in jail at Clyde until 1938. The majority of crimes in the early 1900s involved chicken and hog stealing. Chicken stealing could result in six months on the chain gang or a $200 fine. There was also some moonshining, fishing on Sunday, and a couple of charges of adultery. More serious offenders were moved to a state prison or hanged.

Many old-timers whisper of the hanging tree. Tommy Darieng’s father supervised the jail during its last six years, before it was moved to Pembroke. He doesn’t remember hearing of any hangings on the notorious tree, but he does recall his father talking about the last executions, which were conducted inside the jail before his appointment.

Recorded history of the Clyde area dates back to the 1750s, when settlers began moving into the Canoochee region. The Wises were among the first to settle in Clyde, arriving at Rice Landing. In 1814, the area was named the county seat. Land was purchased from the Harn family—original owners of The Ford Plantation in Richmond Hill—to build a courthouse. On maps of the era, the town was identified simply as Bryan Courthouse. Some historical accounts refer to the area as Eden. It was officially named Clyde in 1886.

Vernacular architecture speaks volumes about the culture and lifestyle of an area. Timber from the surrounding lands was used for the construction of farmhouses and outbuildings. Houses were built off the ground with a long hallway running from the front door to the back for ventilation. Typically, the homes had several rooms to accommodate large families. Many included smokehouses, chicken coops, barns, outhouses, and small gardens. Yards were kept grass-free and swept clean with a gallberry brush broom. Some in our group still recall those brooms—and how they didn’t dare walk across the yard when it was freshly swept.

In the early days, most made a living by timbering and growing rice. Later, farmers grew cotton and tobacco and raised chickens and livestock. Goods were transported from landings along the Canoochee to Savannah to be sold. Over the years, several businesses opened, including general stores, a sawmill, and a turpentine still.

There, the evolution stops. For those who remember it, Clyde will forever be fixed in time—in the 1930s. Around 1940, the government took Clyde and the surrounding settlements for use as a military camp. Those who owned property were paid what the government deemed fair value—but only after they had moved. Those who rented or lived in family homes passed down for generations had little or nothing.

“Some people tore down their houses and used the lumber to build a new one,” Ada remembers. “The government was only going to tear them down anyway. We were lucky; we were able to move our house. They gave us $500 for the rest of the property.”

The earliest settlers around Clyde witnessed the birth of the country and, with pioneering spirit, helped build it. In the mid-1800s, Clyde witnessed the dividing of the nation and suffered greatly as Sherman burned or confiscated everything in his march to the sea. There are many stories of acts of valor during the war, and of how the people of Clyde banded together to rebuild their spirit and their town after the devastation.

In the end, they lost the town—or bravely laid it down in sacrifice—but they never lost their spirit.

Most could not dwell on the significance of what was happening. They faced it as one of life’s challenges—one they were determined to overcome.

Billy Speir, Thelma Wise Speir’s husband, waited and watched as they tore down the town, home by home and building by building. When the church bell came down, he took it. From the Clyde Chapel in Richmond Hill, it continues to ring.