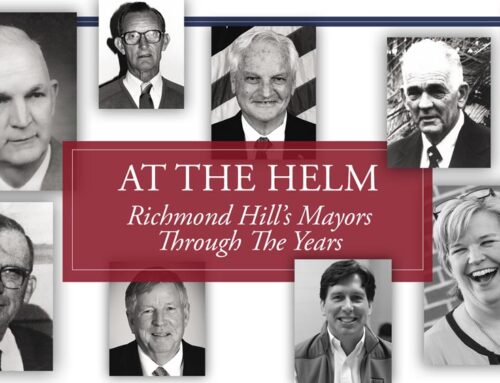

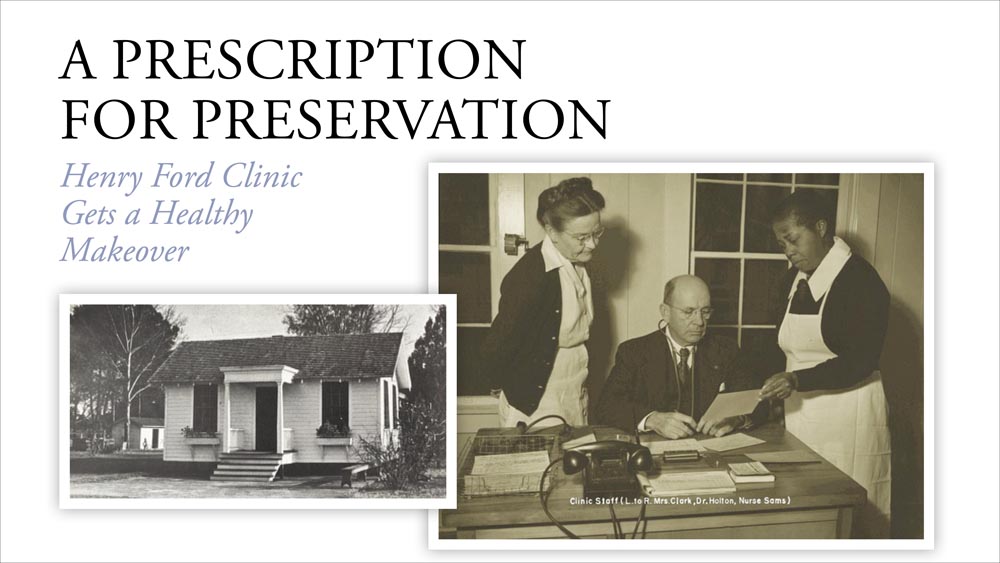

A Prescription for Preservation

Henry Ford Clinic Gets a Healthy Makeover

WORDS BY Christy Sherman PHOTOS Courtesy of Richmond Hill Historical Society

In the heart of Richmond Hill, Georgia (formerly Ways Station), is a tale of compassion, dedication, and community. A small building with a big story has recently taken on a new life thanks to its new medic, Josey Jones’s unwavering commitment.

During the early 1900s, many of the residents of Ways Station struggled with poverty. The children, especially, were faced with severe health challenges like hookworms, and no doctor was within a 25-mile radius. Malaria cast a long shadow over the community to the extent that “chills and fever” had become a regular part of life. When there were means to acquire it, Quinine became a fundamental aspect of a child’s existence, as much as his daily meal.

Ms. Allethaire Ludlow Rotan, a winter resident of Ways at her home, “Folly Farms,” had the heart and financial means to make a difference. She was a prominent figure in high society, devoted to various philanthropic and community projects. Married three times, she was a widow of the late financier, George W. Elkins, and of the late Philadelphia District Attorney, Samuel P. Rotan. Following the passing of her second husband in 1919, it was reputed that she inherited a substantial fortune, estimated to be between $20 and $30 million.

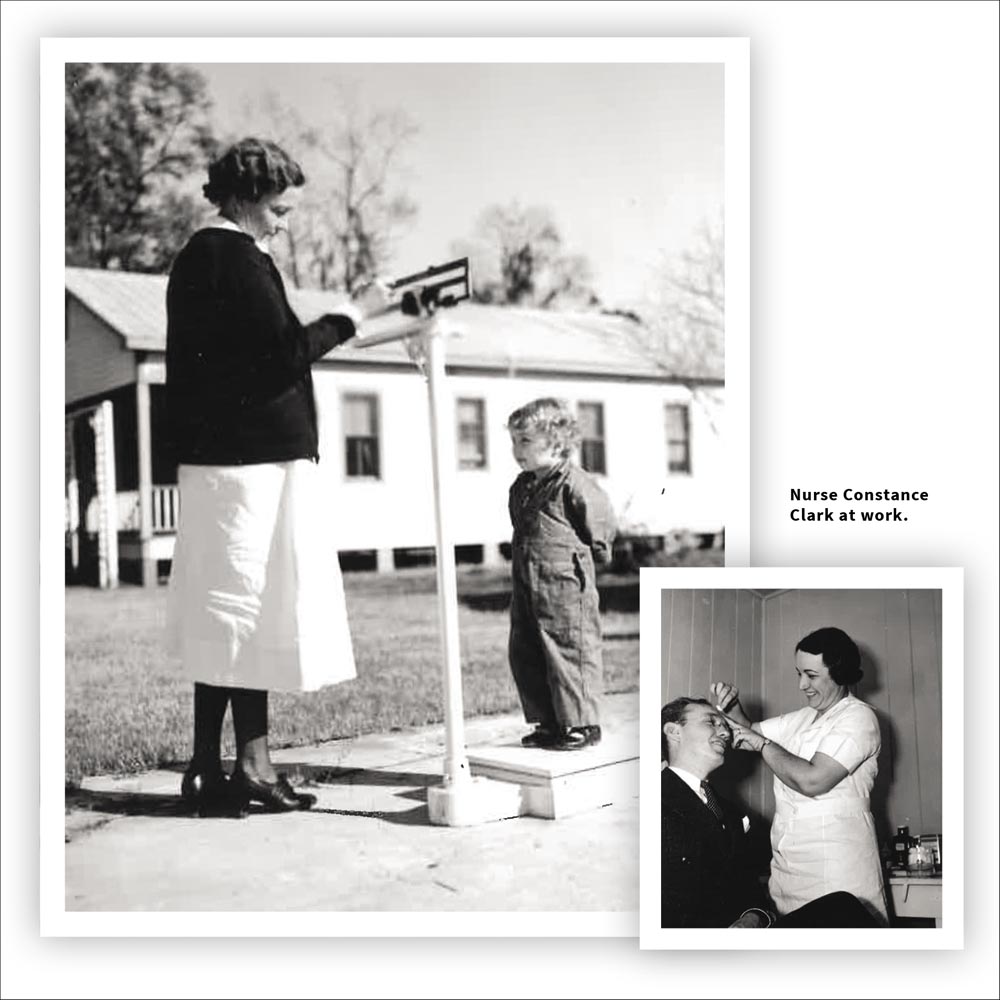

In 1929, Ms. Rotan approached Dr. C.F. Holton from Savannah to discuss the conditions in Ways Station. She proposed compensation for a nurse to relocate to the area and offered to cover the salary of a physician who could conduct educational programs. Dr. Holton offered to take on the role of medical director without compensation, while Dr. Eugene Baker, a pediatric specialist, committed to conducting two weekly visits. Mrs. Constance Clark was selected as the nurse and willingly agreed to relocate to Ways Station. With a professional staff now assembled, Ms. Rotan announced the new healthcare service for children on May 1, 1930, under the name of the Ways Station Health Association. This new program was a gift of hope for the less fortunate residents of Ways.

Mrs. Fannie Wetherhorn took on the role of secretary/treasurer for the Association. She took care of administrative duties as well as fundraising. Along with the others, one of her most significant challenges was motivating hesitant parents. Her dedication and tireless efforts ultimately led to winning over a somewhat skeptical public, convincing them of the invaluable benefits of the program.

Without a dedicated clinic building, healthcare workers had to make do with makeshift setups within local schools. By 1932, the Association identified the need for medical care among the adult population, leading the pediatrician, Dr. Baker, to step down from his position. Dr. Holton assumed responsibility for ensuring that both adults and children could receive treatment. Dr. H.F. Sharpley, Jr. joined the medical staff and distinguished himself, particularly in the field of prenatal care.

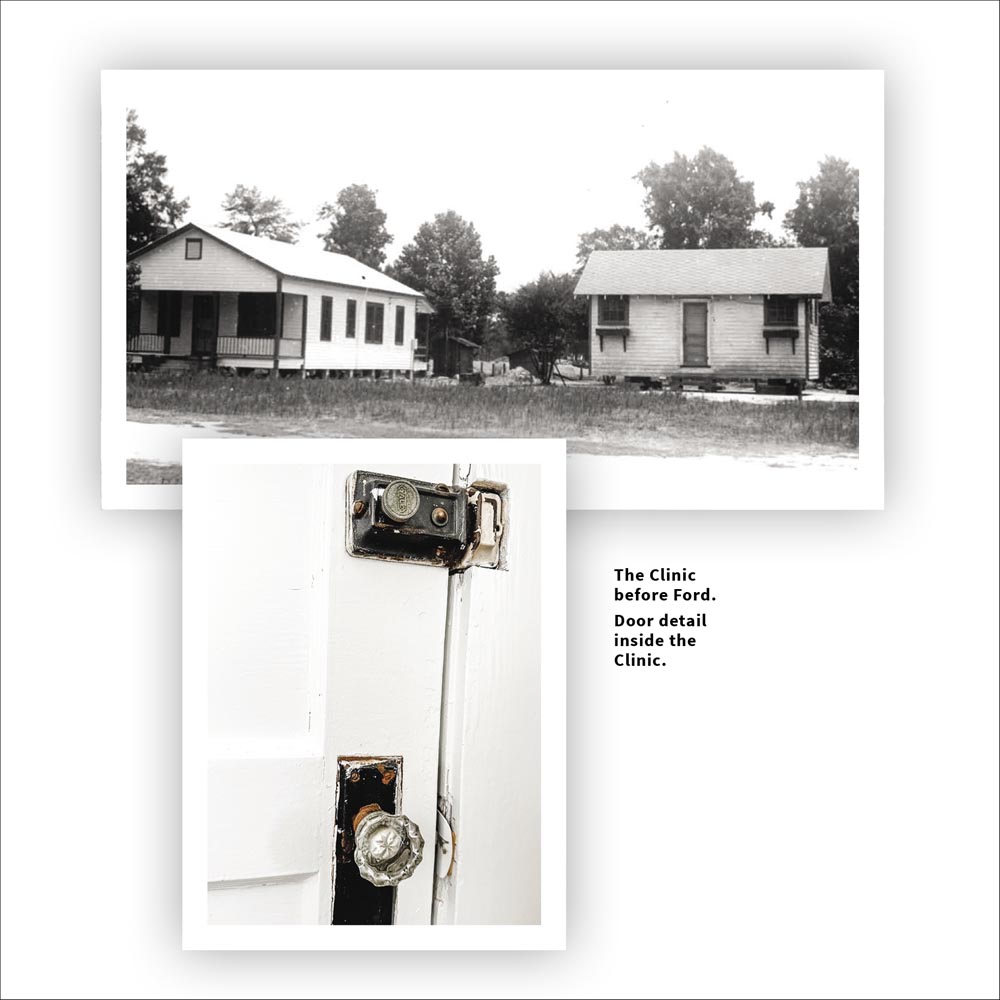

The same year, the Association purchased an old one-room store on a small tract of land (near the site of the present-day Ford Community House). Mr. William Ludlow, Ms. Rotan’s brother, was instrumental in getting the building ready for patients and constructing benches for the waiting room and tables for the staff. The open storeroom was partitioned into sections using sackcloth curtains, creating a waiting room and examination areas. The number of patients steadily rose at the new location, and both doctors and Nurse Clark consistently administered care for a diverse range of conditions. They addressed issues like syphilis, hookworms, malaria, diphtheria, influenza, and tonsillitis and even undertook dental and vision corrections as part of their comprehensive healthcare services.

But as the demand for services increased, so did the financial strain. The Association organized fundraising initiatives like box lunch picnics and entertainment events, but the proceeds were limited, making it difficult to meet growing operational requirements. Regrettably, due to financial constraints, they were forced to discontinue Dr. Sharpley’s position and reduce Dr. Holton’s clinic hours to once a week. Amid the harsh economic backdrop of the Great Depression, Ms. Rotan deemed it necessary to withdraw her financial support in 1935, and the clinic was at risk of closing.

The cause of Ms. Rotan’s withdrawal remains uncertain; however, she proposed a potential solution: having her neighbor, Henry Ford, assume control of operations. The automobile magnate and his wife, Clara, had amassed large amounts of land in Ways Station over the past decade. Their commitment to the community was already evident through many philanthropic projects, which included the construction of essential infrastructure and by creating employment and educational opportunities for residents. Given the extensive workforce under the Fords’ wing, managing the clinic may have seemed like a natural progression.

The clinic shut down for approximately ten days while Ms. Rotan and Dr. Holton appealed to the Fords, emphasizing the potentially severe impact the closure would have on the people of Bryan Neck. Henry Ford’s decision to take over the clinic seems to align with his commitment to healthcare accessibility, particularly considering his ownership of the Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Michigan.

Acquiring ownership almost precisely five years after Ms. Rotan initiated the healthcare program, Ford immediately built on the foundation established by the Association. He demolished the former store-turned-clinic and moved the newer clinic building across the street. In addition to cosmetic changes like enlarging all of the windows, Ford changed the two original rooms into a waiting area and added a doctor’s office, a consultation room, and a bathroom to the rear. Ford added Nurse Ella Reid to the staff, who became a cherished member of the Bryan Neck community like Nurse Clark and Dr. Holton. Nurse Clark and Nurse Reid began administering typhoid and smallpox vaccinations to all Ford employees and their families.

Services and medications were offered free of charge to all 2,000 residents in the area, regardless of their affiliation with Ford. People began coming from outside of the area, within a 10–15 mile radius, including from Camp Stewart. No one was turned away. Ford even instructed Nurse Reid to make a 60-mile drive to Darien once weekly to check on “Aunt Jane,” a former enslaved woman being cared for by the Fords. Between May 1, 1935, when Ford assumed ownership, and May 1, 1940, the clinic’s patient count surged to 11,064, doubling compared to the initial five years. Moreover, a number of patients were offered services at the Henry Ford Hospital in Michigan, including transportation if they needed more specialized forms of treatment, all free of charge.

During this time, Dr. Holton’s primary worry centered around the persistent number of malaria cases, with a significant portion being the alarming aestivo-autumnal type, referred to as “blackwater” malaria, which can result in severe anemia, kidney damage, and even death if not promptly treated. Ford granted Dr. Holton complete authority to proceed with anti-malarial efforts, with the support of the Georgia State Board of Health, which sent two malaria specialists to oversee the work. Additionally, 21 nurses were hired to participate in the campaign. From January to September of 1937, the nurses took blood samples from every resident of Bryan Neck through home visits and gave pills to cleanse the blood of any disease carriers. If an individual received a positive test result, they were asked to take a five-day treatment of the drug Atabrine. In a 1952 interview, Dr. Holton recalled, “We placed the largest single order for Atabrine that the Winthrop Chemical Company had ever received. The representative came to see me and said, ‘I understand you want a large amount of Atabrine.’ I said, ‘Yes, I do.’ He said ‘How much do you want?’ I said, ‘A barrel full.’ He nearly collapsed. We bought it and also bought a barrel of Quinine capsules. We kept the barrel of Quinine capsules available to the community at any time. Any person who wanted Quinine in addition to Atabrine could come up and fill his pockets with them if he wanted.”

If you worked for Henry Ford or lived on Ford property and tested positive, taking the treatment was required. A nurse personally delivered a pill first thing each morning. She would return after lunch to administer a second pill and leave a third dose for them to take at night. Children who could not take Atabrine were given Coco-Quinine as an alternative. Thanks partly to an ambitious educational campaign, there was minimal opposition to taking the pills. In the rare instance of dissent, individuals usually complied due to the risk of losing their employment and home. However, the severity of malaria symptoms drove people to the point where they were willing to attempt almost anything to improve their condition.

After two weeks, blood tests were repeated, with only a small minority showing positive results. Those individuals were given follow-up treatment with a drug called Plasmochin until they, too, tested negative. In the meantime, Ford’s dedication to the eradication of malaria went beyond the clinic’s walls. He oversaw an extensive drainage project to eliminate the breeding grounds of disease-carrying mosquitoes. Despite the challenges posed by families moving in and out of the area, by July of 1940, only one positive case was reported and treated—a man who worked for Ford but did not live on Bryan Neck.

Through these efforts, the team successfully eliminated malaria from Bryan Neck, and the State Board used these effective methods to eradicate the disease throughout Georgia. Dr. Holton received recognition and requests for copies of his articles on controlling syphilis, malaria, and hookworm in the South from universities and health departments across the United States and three foreign countries.

In a report dated August 1940, Dr. Holton documented the clinic’s influence and effects: “Since the Clinic was established there has been a marked improvement made in the entire population, but particularly in the children. This has been due to two things: improvement in their health as a result of the clinic work, and, of far more importance, improvement in their social surroundings as a result of the benevolence of Mr. Ford, who has provided them with jobs with which they earn enough to buy proper food, with schools for education, and with a chapel for religious instruction. The combination of these factors has changed the population from a sickly, suspicious, illiterate and undernourished group into one of the healthiest communities in Georgia in which the general population is well-fed and satisfied. The children now would compare favorably with any group in the world, physically, mentally and in every other particular. To one who has observed it throughout, as has the writer, it has been a truly amazing transformation and each graduating class at the high school is a living monument to

Mr. Ford and Ms. Rotan, who began the clinic work.”

Following the death of Henry Ford in 1947 and Clara Ford in 1950, the clinic continued to operate but experienced notable changes. Managers of the Fords’ estate significantly cut clinic hours, shifting from a daily schedule of two hours to just one hour per week. They also reintroduced medication fees and restricted clinic access to Ford employees only.

On September 6, 1951, Ford’s grandson, Benson, issued a letter to all employees to formally announce the termination of operations. The Fords’ land holdings were subsequently listed for sale the same year. Mr. Gilbert Verney, a businessman from New Hampshire, acquired the clinic building and other properties, including the two Ford employee housing developments and the Fords’ home, Richmond Hill Plantation. Mr. Verney, with a background in the textile industry, intended to construct a new mill in the area. With more interest in the land than the structure, Verney sold the clinic building to Dick and Pearl Carpenter with the condition that it be relocated. The clinic building

was to be moved again—this time several miles east on Bryan Neck Road, near Belfast Keller Road.

Dick and Pearl, both former employees of Henry Ford and former clinic patients, transformed the once sterile examination rooms into warm and inviting spaces for their home. Over the next five decades, they created family memories within the walls that had witnessed countless significant moments from the past. Notably, Richmond Hill’s current mayor, Russ Carpenter, is the grandson of Dick and Pearl. “During my childhood, Grandma often shared stories about how these rooms were once used as a clinic,” Carpenter reminisces, adding, “Many people from the Ford era still referred to it as ‘the clinic’.”

Following Pearl’s passing in 2001 at the age of 88 and Dick’s passing in 2004 at the age of 95, the property remained in the family’s possession until 2022, when the extended family decided to sell it.

With a commercial zoning designation and the absence of protective measures for landmark structures in Bryan County, the Richmond Hill Historical Society leaders had reason for concern. “We were nervous about what might happen to the clinic if it were to be acquired by an unknowing buyer with intent to modernize or demolish it,” admits Amy Mitchell, president of the Richmond Hill Historical Society, reflecting on those uncertain times. “Our mission focuses on the preservation of our area’s rich history and we were desperate for the structure’s historical significance to be respected and preserved.” Amy and others contacted the Realtor and provided her with a comprehensive history, photographs, and other information to educate potential buyers about the building’s story. The Historical Society even attempted to find a way to save the structure themselves, but needed more time and funds.

The Realtor complied with the request and diligently passed the information along to any prospects. Fortunately, a few passionate buyers emerged, captivated by the clinic’s rich history. The Historical Society began fielding calls from potential buyers asking for more information. Ultimately, the clinic found its guardian angel in Ms. Josey Jones, a resident of Richmond Hill.

Josey had been looking at commercial real estate for some time when she saw this property for sale. “When I first met the Realtor here,” she recalls, “she asked about my plans for the building. I confessed I wasn’t entirely sure, considering its age and condition. That’s when she shared its history with me. Once I heard that, it was an instant thing. I knew I had to have this building.” With roots deeply embedded in Richmond Hill, Josey suspected her own family might have been patients here. As a nurse herself, she had profound respect for Henry Ford’s contributions to the community and felt compelled to be a part of preserving that legacy.

The purchase was a leap of faith; sold “as is,” Josey couldn’t inspect the building thoroughly beforehand. “I didn’t know if there were termites or really the condition of anything I couldn’t see,” she admits. “But I knew I had to save this building.”

With a passionate commitment to preserving history, Josey embarked on an ambitious restoration journey. Historic photographs and documents became her guiding light as she meticulously returned the building to its Ford-era appearance. She replaced outdated electrical and plumbing systems, restored rotting wood, and brightened the interior and exterior with a fresh coat of white paint, among various other improvements. Josey restored the original front porch, railings, and flower boxes to match historic photographs.

Inside, the clinic has found new life as “Back in the Day Antiques & Things,” a charming boutique that welcomes visitors from near and far. Interpretive posters on the walls showcase the clinic’s exciting story, while an antique scale and a vintage first aid kit are on display as a nod to the clinic’s past. Handpicked antiques, local artwork, and unique jewelry carefully curated by Jones are for sale. New friends and curious neighbors drop by regularly, leaving with a newfound sense of community pride. “People come in, and they just stay awhile,” Josey noted with a smile. “This place truly has taken on a life of its own.”

This story serves as a reminder of the power of individual dedication and community preservation. Through its new purpose, the clinic is again a cherished part of Richmond Hill’s rich heritage. •

Editor’s Note: Josey asked me to share a special thank you to Michael McGaughey and Tracy Shaw who have meticulously restored the building for her, and to Christy Sherman for her research and knowledge.