Finding Ford, Finding You

WORDS BY PAIGE GLAZER

2023 ANNUAL ISSUE

What will the future read about in books documenting this era here in Richmond Hill, Georgia? We can only hope the story that has spanned centuries—leaving in its wake a fascination that has yet to fade amongst us will still be there for our grandchildren’s children.

The undeniable draw of this place has seemingly always existed. Read it in any history book about any century and look at the stats presenting today—her allure is alive and well—so well that those who have been here for a lifetime say they would never dream of leaving. And those who have been here for a short while say they wouldn’t either! There were battles amongst those who came to lay claim and those who already called our precious coast home noted as early as the 1500s. Be it the accidental landfall on a nearby island, a King’s grant and challenge to colonize the new world, the fertile soils for planting rice, cotton, or pine, the idea to better a desolate community, the top-rated schools for educating youth, or just the stunning vistas along the river shore, the reason for coming might vary but the character of the inhabitants (past and present) does not. Their respect for the land and their attitudes for one another almost make us look as if we have all been cut from the same cloth as those before us.

I can’t say if I would feel this way if I were from another location in the world, but the salty air that fills my lungs and the glitter of the rivers gives me such a warm and deep sense of pride that like so many others, I will spend all of my days looking for ways to leave this place better for the next generation than as I have enjoyed it.

Glen McCaskey said it well in The View from Sterling Bluff, “Great volumes of water have flowed past its [Richmond Hill] serene setting as has a proportionate share of drama. The river is quieter now then when it used to be one of the two main arteries of transportation into the Georgia frontier. Thousands of men have come and gone but men still fish for shad in the passing waters. Things are different but things are much the same as well…”

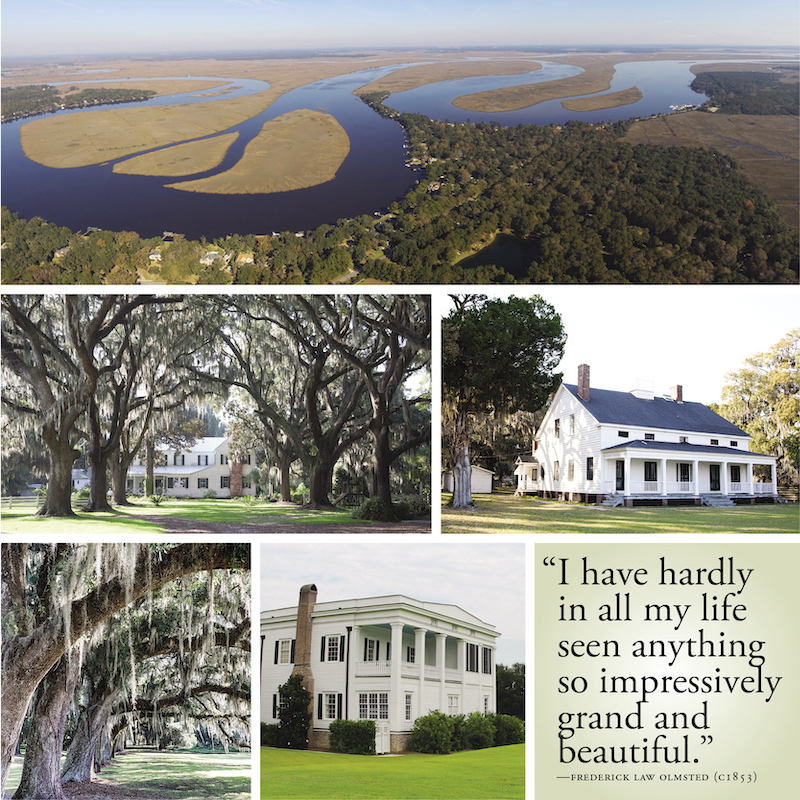

In all of the documented past, the community characters made intentional decisions to build upon and enhance the prior generation’s efforts. One of the earliest examples of this, still visible today, is John Harn’s planting of the picturesque Live Oak trees we see streaming with moss in the allees in front of the Ford Mansion and the Clubhouse at The Ford Field and River Club (formerly the site of Cherry Hill Plantation). They create the most glorious scene during the golden hour. Who knows if he planted them with us in mind, but people are thinking ahead today; the Coastal Bryan Tree Foundation plants trees that will one day be admired in the same light. I don’t think much has changed in the 166 years since Frederick Olmsted wrote about our area and I don’t think I can say it any differently when it comes to those oaks:

“I have hardly in all my life seen anything so impressively grand and beautiful.”

—Frederick Law Olmsted (c1856)

John Harn was one of the most notable grantees of what would one day become the Ford Estate. It was about 248 years ago when he was granted 500 acres on Sterling Bluff—likely because of his English loyalty in America during the 1740 attack on St. Augustine. He named it Dublin Plantation. It is assumed that he planted the aforementioned oak trees as they are planted in the shape of an “H” evident today from a bird’s eye view. In just two short years, these trees will have witnessed a quarter of a millennium of history on the bluff where their roots were planted—layers upon layers of time and activity, all along admired the same. This makes me think about what legacy I will leave behind.

From Harn’s hands, Dublin Plantation became John Maxwell’s, before the Clay Siblings in 1829 (who changed the name to Richmond on the Ogeechee). These two families were intertwined throughout the next two generations in many well-known historic structures and locations along Bryan Neck and the Ogeechee River. Their final resting place can even be visited at Burnt Church Cemetery.

Along the same river is the story of the end of the Civil War. The area was now called Ways Station as the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad came to town (the track located between Sawmill Plaza and Plantation Lumber today). Some say war came on that railroad.

Ways had quickly become known as one of the most prosperous landscapes in the nation. The river, servicing her people with a way to import goods and send a wealth of exports including cotton, rice, and timber added rail to its tool box. During the Civil War, the Union Army referred to Bryan Neck as the “Ogeechee Bread Basket,” and their mission was to destroy it. When Union troops arrived, the very successful Confederate Fort McAllister defended the bread basket by water, but left the door open by accident in terms of an attack by land. General William T. Sherman marched his troops down what is probably now Highway 144 and sat back in one of the prettiest locations on the Neck, The Seven Mile Bend, to watch the fort fall. In his path, he left a burning mess of many plantation homes, the handful we are blessed to admire today, are all that was left.

Most of the planters moved away and what was left of their plantations fell into disarray. Dark days fell upon the people of Ways and Bryan Neck. The early days of modern history in Richmond Hill were extremely poor, characterized by moonshine stills, run down barns and farms, hookworm, malaria, and a community of mostly unemployed people, all they had was their river to sustain them.

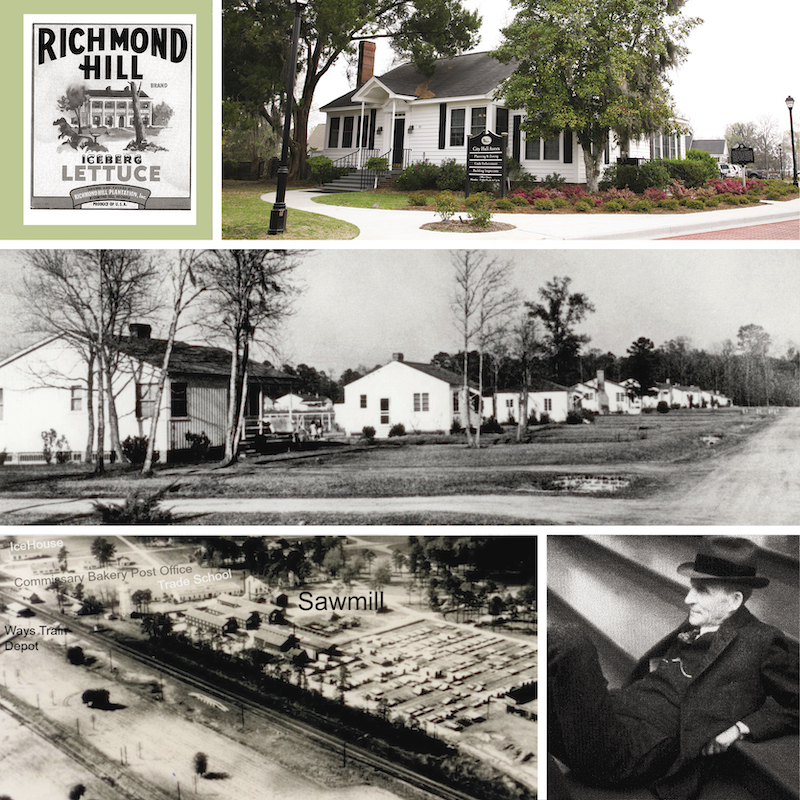

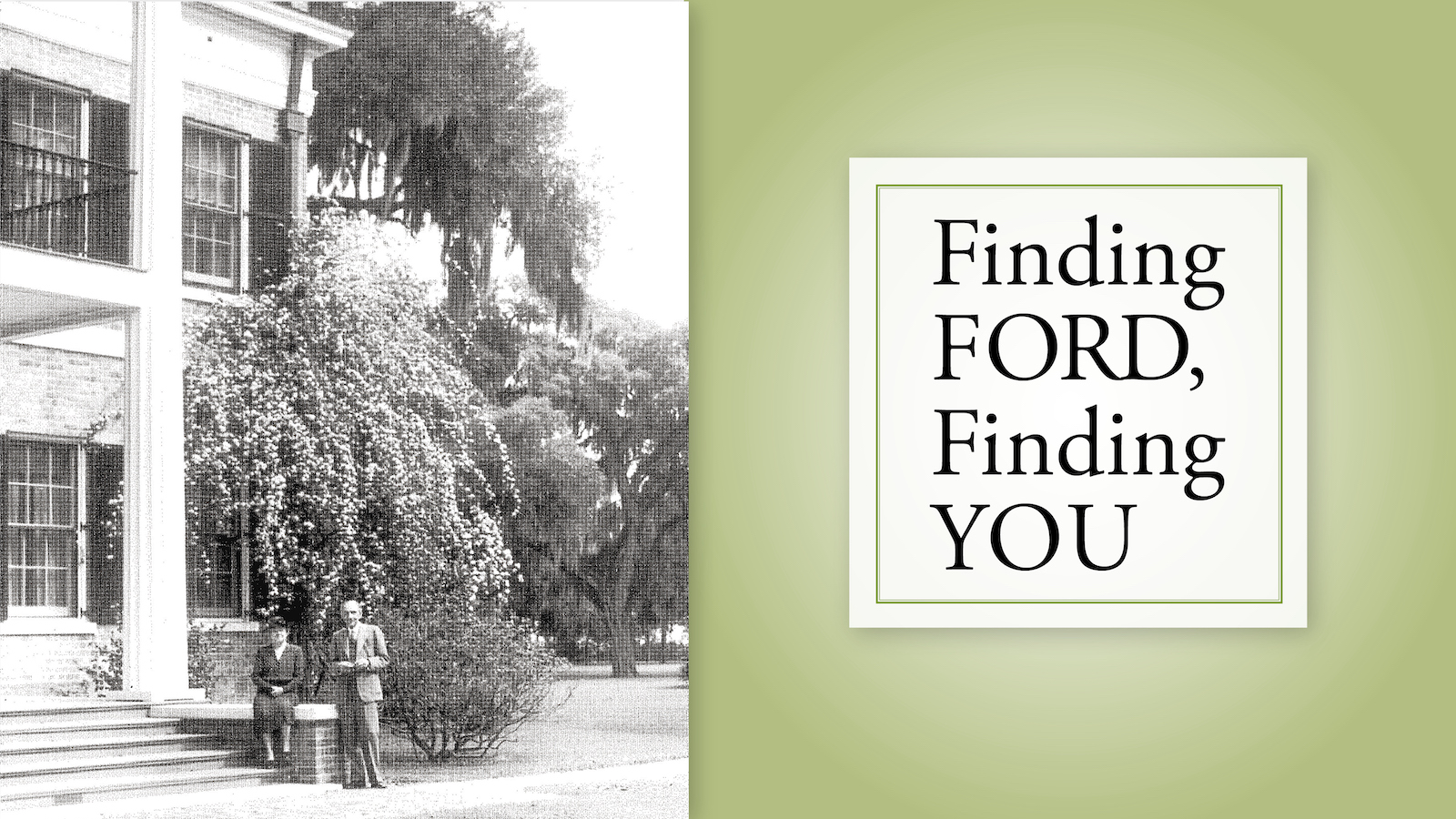

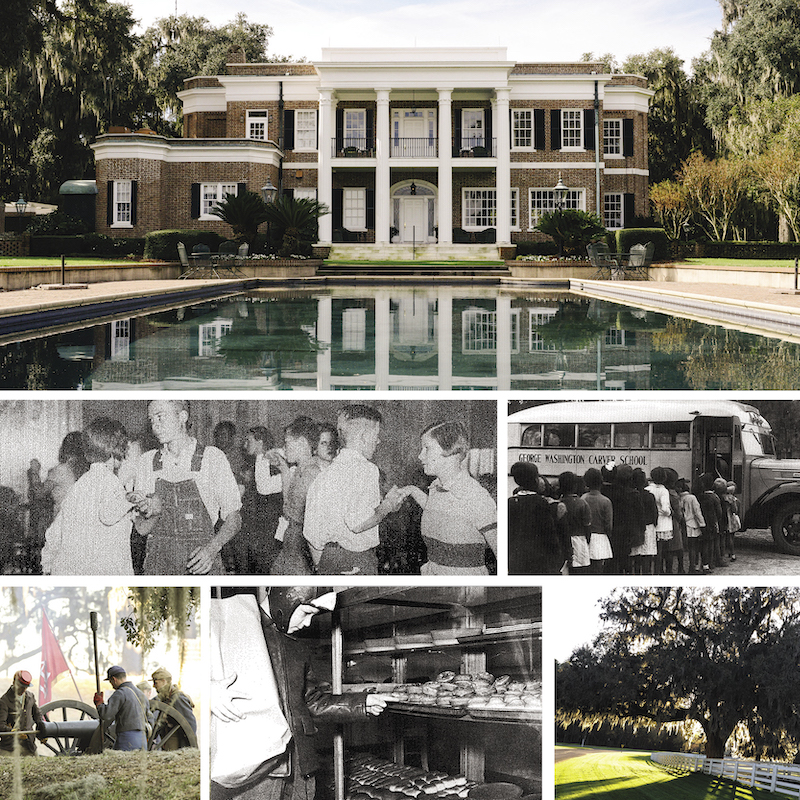

The river would be how auto magnate Henry Ford found this place, bringing with him dramatic social and economic reformation. In 1917, on a yacht cruise with John Borroughs, he saw it for the first time—plush with timber and serene beauty. Ford began acquiring property in 1925. Ten years later, on a bluff overlooking the river on which he arrived, he and Clara built their winter home. Dublin (Richmond on the Ogeechee) once sat in the same location they chose some 200 years earlier, just up the middle of the gorgeous oaks planted in the shape of an “H.” They called the entire Ways Station / Ford Farm properties “Richmond Hill Plantation.” It should be said that the “Hill” has no documented purpose. If I were the betting type, my money would be on how high up the bluff upon which he built his home looked from the yacht where he first viewed it!

292 buildings were built at Richmond Hill Plantation, including all of the necessary investments one would expect for a town to be self-sufficient. Ford created jobs for the people building a Post Office, Sawmill, Community House, Power House, Chapel, Trade School, Kindergarten, Commissary, Ice Plant, Bakery, and more. People were offered health care and malaria and hookworm were eradicated, swamps were drained and children were educated, all at his expense. The timber he saw from the river had intrigued him. Could these soils grow rubber perhaps? Ultimately, the soils proved to be perfect for pine and lettuce, but nothing that would supplement his automobile lines. Ford owned over 75,000 acres of land on Bryan Neck, he rehabilitated pieces of history like Fort McAllister and various plantation homes along the rivers, bringing them back to life. And much like the people throughout our history and today, when he died, he left this place much better off than he found it.

Nearly 100 years since this place found Ford, it continues on a trajectory of betterment, finding the likes of you and me, and a slew of new neighbors. The people may have been led here by their professions—commercially fishing the waters, timbering the forests, building neighborhoods, manufacturing quartz surfaces or electric vehicles—but like those before us, we are all leaving a mark on the future of Richmond Hill. We are forming organizations to protect and preserve the stories and structures built before us, sometimes we even re-enact history so to share the stories of the past, we’re planting trees back as growth pulls them down, cleaning the rivers, and teaching the children how to be a sustainable community. Intentional actions are being shared each and every day amongst a community that will ultimately preserve what we’ve all been drawn to, the likes and the beauty of the prettiest little peninsula on the coast, and her incredible flowing rivers.