From the Archives

Plenty Happened Here

ORIGINAL WORDS BY CHRISTY SHERMAN ADDITIONAL WORDS BY PAIGE GLAZER PHOTOS COURTESY OF RICHMOND HILL HISTORICAL SOCIETY

SUMMER 2022

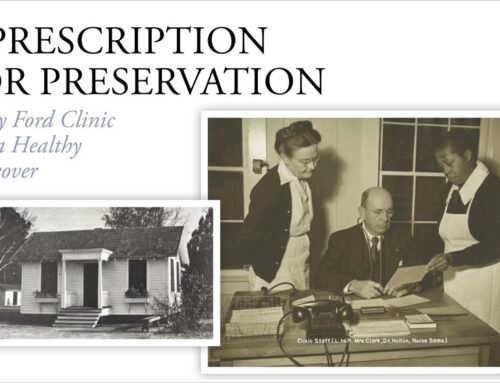

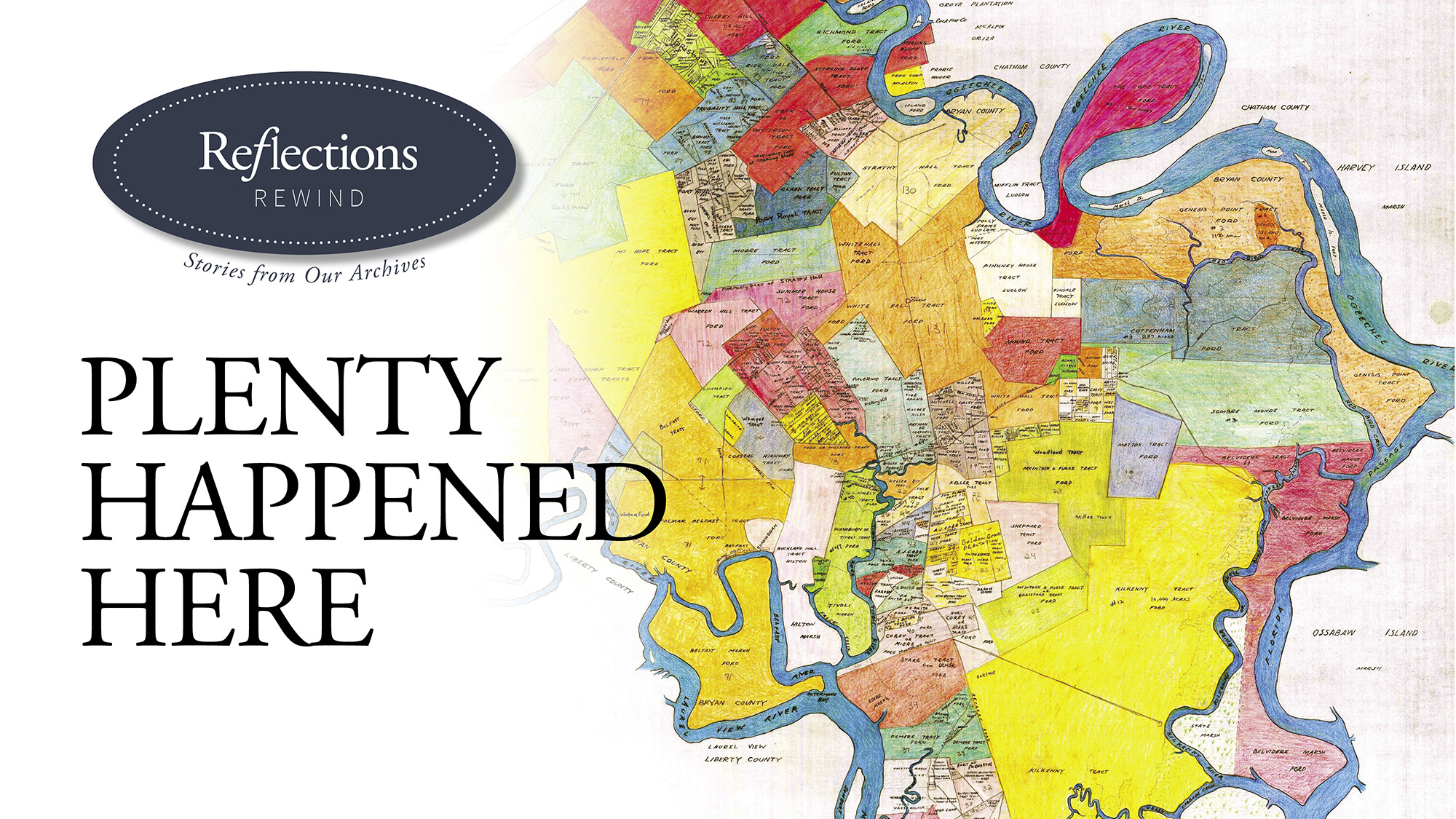

The Richmond Hill Historical Society’s mission is to preserve the history of Bryan Neck, educate and connect the past to the present. History can be dry, but this organization helps guide all of us into a future where heritage and history remain prominent in a modern, vivacious and growing community. There are so many interesting accounts written about Bryan County, and many have never been published. One never knows who or what might walk through the doors of the Richmond Hill History Museum, and often the stories they leave behind wait in the archives to be told. This historical recount was from a copy of a written narrative by Ben Green Cooper, circa 1936, and was shared with the 2012 Richmond Hill Historical Society Board of Directors by Danny Brown, then director of the Fort McAllister State Park.

This history was written before Interstate 95 was built and US Highway 17 was the major corridor for traffic along the east coast. “Mr. Cooper’s introduction to his book grabbed my interest,” says Christy Sherman, Executive Director of the Visitors Bureau. “In fact, everyone who has read the first three pages says, ‘I want to read more!’” Reading about the events and people who helped shape the Richmond Hill and Bryan County we know and love today is captivating. Enjoy a few snippets, and if you yearn to learn more, visit the Richmond Hill History Museum!

Introduction to the History of Bryan County Georgia by Ben Green Cooper

The Florida-bound tourist, striking the northern most point of Ford Farms at the Bamboo Farm on the Ogeechee Road, and riding through and by the 70,000 acre estate for 11 miles before entering Liberty County, is inclined to believe “Nothing ever happened here.”

He sees only long, green lined stretches of fast highway, leading through open fields, pine barrens, and dark swamps, a long walk if one runs out of gasoline.

Suppose he pauses long enough on Ogeechee Neck (now called Bryan Neck) to ride the sandy roads and see the grass grown fields, stately forests of oak, hickory, magnolia, and pine; the swamps of cypress and black gum, the creeks and bays where “nothing ever happened.”

Suppose he gets out of his car and wanders through lanes of magnificent 200 year old oaks, spreading their limbs in gigantic umbrellas over broken ruins of brick and tabby, or stands on soaring bluffs and sees vast expanses of marsh relieved occasionally by creeks, canals, and rice dams.

Suppose he chanced upon the sturdy earthworks of Fort McAllister, or the time defying structure of Kilkenny House, or the almost forgotten graveyards of the Maxwells, the Butlers, the Youngs, the Cubbedges, and the other great families of Ogeechee Neck.

Even then, unless some kindly guide took time to tell him of the great men of long ago, he would go on his way, still believing “nothing ever happened here.”

And yet, plenty happened here.

Ogeechee Neck, like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, has her glorious past.

Her sons played their parts in the drama of America’s birth, development, and progress. Her friends were among the great men of their days, names familiar to every school child.

Her story comes piece meal from old books and records. A fragment from here fits with a fragment from there, and the jig-saw puzzle slowly works into a pattern showing the lives of those who helped to build a struggling colony into the “Empire State of the South.”

Jonathan Bryan, from South Carolina, supported James Oglethorpe when he founded the British colony of Georgia. Our county is named after Bryan. What a man was he! Kindly, wise and generous, a heroic figure against a background of intrigue, romance, bravery, and struggle.

Our story tells of Captain James Mackay, master of Strathy Hall and comrade-in-arms of General George Washington and descendant of those who fought with Bruce Bannockburn of John Harn, prosperous planter and politician…of Noble Jones, gentleman, surgeon, soldier, statesman, planter, and patriot of John Reynolds, Henry Ellis, and Sir James Wright, colonial governors of Georgia; of Button Gwinnett and Dr. Lyman Hall, signers of the Declaration of Independence to name but a few.

Our story tells of the forgotten town of Hardwicke and neighboring Fort McAllister, of White Hall and Hickory Hill, of Belfast and Midway River, of the torching and destruction of two wars, and romance under magnolias and sweet laurel.

Many of the planters grew rich from the production of rice, cotton, and indigo. They did this with the use of slave labor. The first rude cabins of early settlements became handsome, well built homes made of brick and native woods.

So, here is the story the tourist missed, the history of a section of the country where “It looks like nothing ever happened.”

Paths of many French, Spanish, and English explorers crossed Ogeechee Neck before the Trustees for the Colony of Georgia launched their plan.

Imprints of early visitors are found on ancient maps that roughly outline the coast and guessed at the interior of what came to be known as Georgia. Almost 200 years before the English colonized this area, the Spanish had laid claim by establishing missions on the islands of Ossabaw and St. Catherine’s.

Old maps show the presence of Indian camps on the mainland near missions operated by the Spanish on the islands off the coast. Remains of ancient mounds are still to be seen in Bryan County, indicating Ogeechee Neck was one of the favorite burial places of natives. Human bones, ornamental urns, and other relics have been brought to light through excavations. (There are examples of relics in the Richmond Hill Museum)

The Ossabaw Spanish mission, Torpiqui, was operated by a Father Rodriquez. On St. Catherine’s Island, then called Guale Island, there was the Assopo mission of Father Aunon.

In 1597, The indians killed Father Corpa at Tolomoto (further south on the coast) and then went to Torpiqui (Ossabaw). It is reported they told the priest “Not to worry himself preaching to them but to call on God to help him.” Father Rodriquez, realizing his end was near, divided his possessions among the Indians, knelt before his executioners, and was slain.

The indians sent a message to the chief of Gaule Island (St. Catherine’s), ordering him to kill the priests at the Assopo mission. The chief, friendly to the priests, tried to warn them by sending a messenger to urge them to retire to the Spanish presidio until danger passed. The messenger failed to notify the priests, and the mission was sacked by the Native Americans.

The Ogeechee River was visited in 1662 by Jean Ribault and his band of French Huguenots. Ribault renamed the rivers of Georgia after those of France; naming the Ogeechee the Gironde.

The first attempt to colonize the Georgia coast by the British was made in 1717 by Sir Robert Montgomery. He termed the area “the most delightful country in the universe” but was unable to colonize within the prescribed time and lost his charter.

Naturalist William Bartram, in his book Travels in North America, mentions crossing Ogeechee Neck in 1750 on his way to Sunbury. His description of the country around Sunbury and Colonel’s Island, south of Ford Farms, is typical of Ogeechee Neck. He mentions viewing large plantations of indigo, corn, and potatoes. He found the water front soil very fertile where mounds of seashells had been thrown up in ridges and dissolved into earth. He reported seeing an abundance of game. Bartram discovered a number of rare trees. He mentioned the famous Ogeechee Lime, marketed ’til just a few years ago. It has almost disappeared in the markets but can still be found in the swamps.

History is a funny thing— often thought of as absolute when it is actually rather fluid. Kind of like the English proverb, “to the victor goes the spoils,” the winner writes the history books, and there is really no way of knowing if the real story is ever told. My history isn’t necessarily your history. How you and I look at the world is molded by our personal experiences and the experiences of our families, as well as our willingness to try to understand what brought us to this point in time in our politics, our wars, and the written or spoken words. As the story unfolds in this book, commissioned by Henry Ford 86 years ago, characters of our storied past were documented as Green learned them. How we the characters of Richmond Hill and Bryan County are documented will leave the readers of the future feeling about the stories we are living today. What will they think? There is a lot still happening here, and there is indeed so much more to come.

Editor’s Note: The snippets were quoted directly from the narrative, The History of Bryan County, Georgia. A copy can be found at The Richmond Hill History Museum.