Pounding Sand

WORDS BY Victor R. Pisano

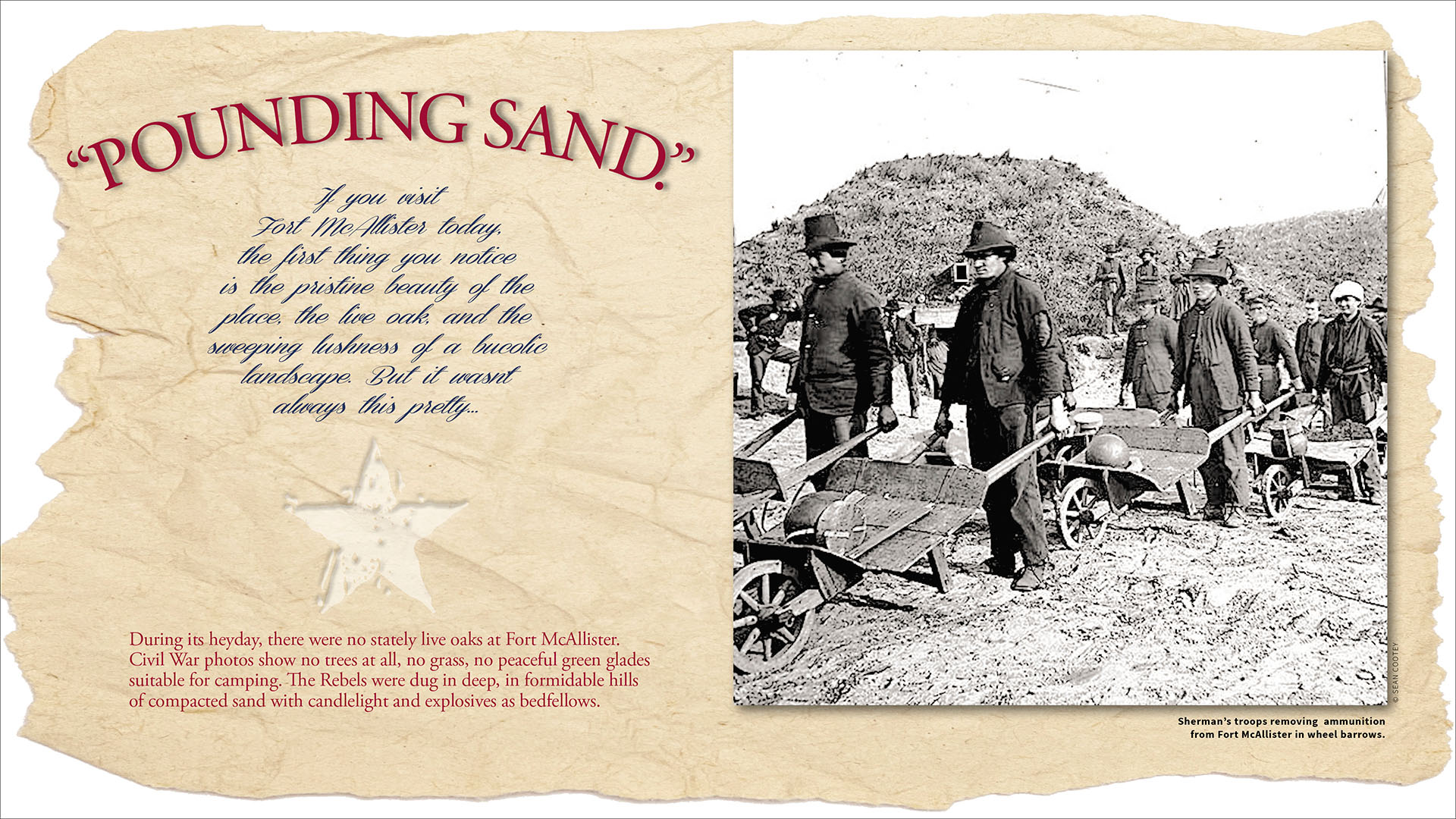

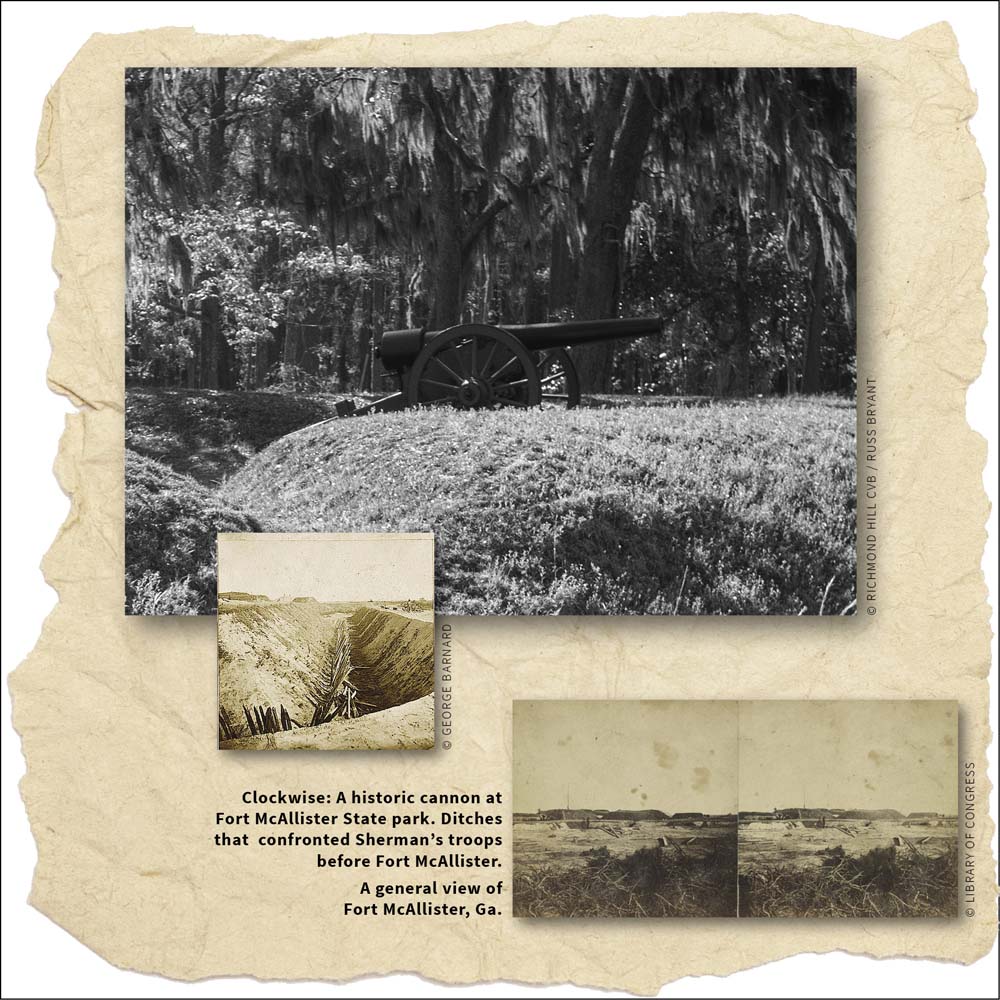

If you visit Fort McAllister today, the first thing you notice is the pristine beauty of the place, the live oak, and the sweeping lushness of a bucolic landscape. But it wasn’t always this pretty…

During its heyday, there were no stately live oaks at Fort McAllister. Civil War photos show no trees at all, no grass, no peaceful green glades suitable for camping. The Rebels were dug in deep, in formidable hills of compacted sand with candlelight and explosives as bedfellows.

In 1864, Fort McAllister was the center of attention in the concluding hours of the Civil War and Sherman’s infamous, “March to the Sea.” In the years 1862–1863, Fort McAllister was attacked by sea seven times and repelled each attack. The fort would just not fall by naval shelling. Fort McAllister was an “earthen fort” built by hired slave labor and compacted into impenetrable mountains of sand. It blocked Sherman’s rear supply line and his personal ambition to take the South on horseback—“his” horseback. Fort McAllister was Sherman’s last obstacle in his quest to level everything to the ground from Atlanta to Ossabaw.

The two-year bombardment from the sea was by no means constant. Not every day was full of the drudgery of war. One garrison officer, William Daniel Dixon, of the famed Republican Blues militia, frequently took day trips to Savannah for both business and pleasure. Dixon often brought lady-friends back from Savannah or hosted them for leisurely tours of the fort with a proper chaperone alongside. He entered one such sojourn in his daily log:

Tuesday, April 19, 1864: “I had a visit from Miss Jane Ferguson, Miss Jane Posey, and the Reverend Mr. Gilbert today. I rode to the railroad station for them this morning and got back here [Fort McAllister] at 10:30 o’clock. We visited the battery and spent a very pleasant time until 2:30 o’clock.”

During those isolated attacks by sea, however, Union state-of-the-art ironclad warships besieged the sandhill fort—hour after hour—with an endless tonnage of cannonball. Most of the shot struck the piled-up sand of the fort with a resounding, “PLOOMPH!”

A “Letter to the Editor” of The Savannah Republican, dated Friday 13th, 1863 observed:

“The Garrison at Fort McAllister, composed of two Savanna companies, from their youthful leader down to the most private soldier, have immortalized themselves. It is not to all probable that heroism greater than theirs, or bravery more sturdy and persistent, will, anywhere, be exhibited during this war.”

Newspaper accounts in the 1860s were the only source of information other than handwritten letters and of course, gossip—which was rampant. Curiously, in surveying hundreds of handwritten letters dating back to 1860–1865, none of them made reference to slavery or what it was that the Blues and the Greys were actually fighting for. The common folk on both sides just kept referring to each other as either, “them Yankees” or “them Rebs.”

Disregarding gossip, the ironclad warships of the Union Navy proved extremely accurate. This was not reported as such in some Georgian newspapers: The Weekly Chronicle and Sentinel in Augusta on March 10, 1863, reported:

“There could not have been less than from 50 to 60 tons of iron ball directed against Fort McAllister during the bombardment, which lasted some 20 hours without cessation, and most wonderful to state the only two casualties were two men slightly wounded. All damages to the Fort have been repaired. The men are in best of spirits. They were, as we learn, cracking jokes at the Yankee’s failed success at shelling, shouting to them, “Too far to the right,” and,“Too far to the left,” as each shell failed to strike the fort.”

There were only two fatalities during this two-year naval attack, the most significant of them being the fort’s commander, Major John B. Gallie. The popular young Gallie took a direct hit to the back of the head from a cannonball while scurrying about the parapets directing his men. The only other fatality by monitor fire, was the camp mascot, a grizzly cat named, “Tom.” The fort itself would just not fall due to its sand-dune construction. The Union Navy, with all its firepower and state-of-the-art ironclad ships of war, ended up only “pounding sand.”

On December 13th, 1864, it took a regiment of 4,000 of Sherman’s 62,000 troops, under the command of Brigadier General William Hazen, to capture Fort McAllister. The fort was defended by only 230 local “Rebs,” including the Republican Blues, a professional fighting militia that had served under the U.S. flag for 50 years before signing on with the Confederacy. Only the ablest of men and volunteers remained to defend Fort McAllister’s vulnerable back door.

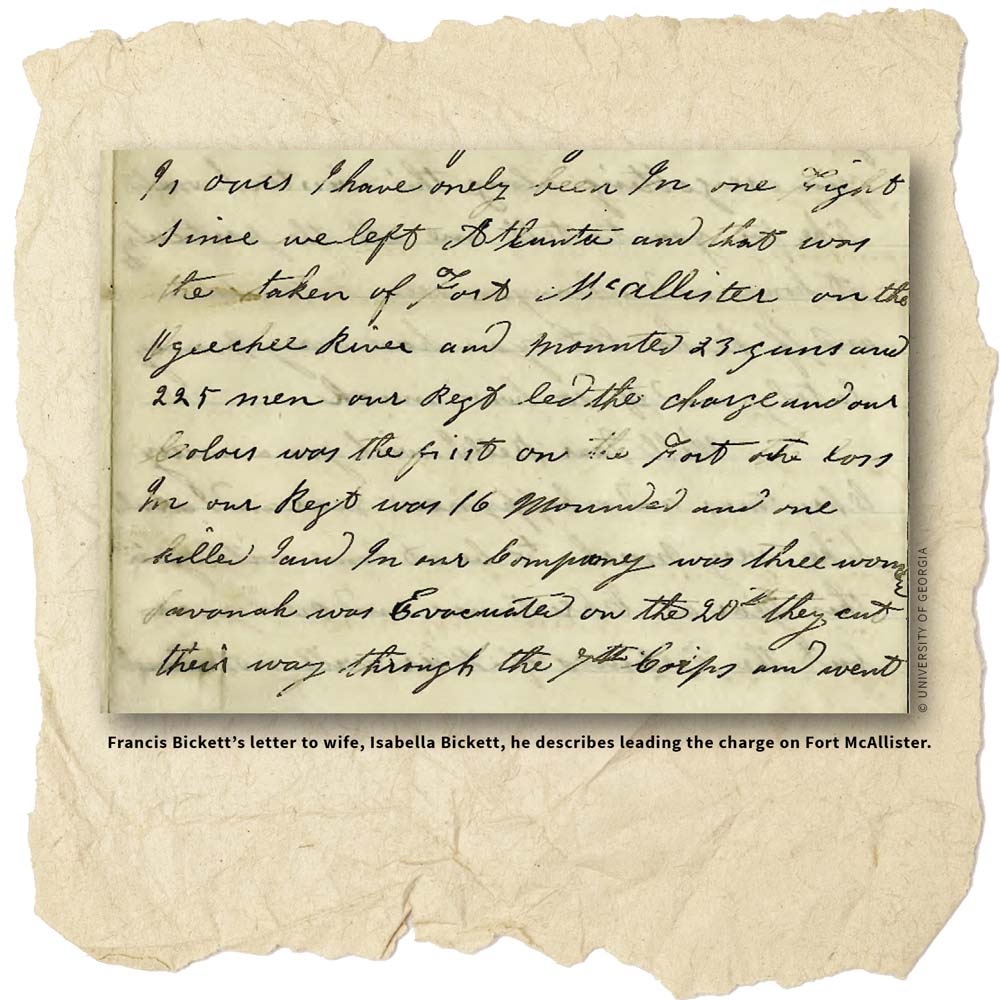

Hazen’s battle charge itself lasted only 15 minutes—not even enough time to start a decent wood-burning fire. The resultant siege was mentioned in a letter from one of the Yankee combatants to his wife: Union foot soldier, Francis Bickett, who wrote to his wife Isabella in December of 1865:

“I have only been in one fort since we left Atlanta and that was the taken of Fort McAllister on Ogeechee River and their mounted 23 guns and 225 men. Our regiment led the charge and our colors was the first on the fort. Our loss in our regiment was 16 wounded and one killed. And in our Company was three wounded. Savanna was evacuated on the 20th. They [the Rebs] cut their way through our corps and went to Charleston, S.C. They left everything they had behind them in their flight.”

But the actual capturing of Fort McAllister was an all-day event. Fort McAllister‘s current Ranger/Historian, Mike Ellis relates, “It started about 8am. Scouting each other out—counting the other side’s guns and position. One officer in Hazen’s regiment started the whole thing off by shooting and killing the camp mule. This made those at the fort scurry for shelter. The actual final attack took only 15 minutes, but the face-off itself was an all-day conflict.”

This was not exactly like the movie where “300” Spartans fought off one million Persian soldiers—but close. Many historians more accurately refer to the taking of Fort McAllister as “the Civil War’s own version of the Alamo.”

Archives will reference Sherman’s attack of Fort McAllister in cold black and white:

Union: 24 Killed—110 wounded.

Confederate: 16 Killed —54 Wounded—195 Captured.

But modern historical accounts can never truly reflect the experience of being there and living through it all. The garrison itself never surrendered but fought until every man was either dead or captured in battle. General Hazen wrote in his own report: “Each man was individually overpowered”— meaning—each man had to be.

Fort McAllister was taken by land, not by sea. In doing so, General Sherman finally eliminated any obstacle to his remorseless “March to the Sea”—literally. Fort McAllister no longer blocked his view of the Atlantic. Sherman was now able to supply the rear of his own indefatigable forces which freed him to advance on horseback to Savannah, uninterrupted, and unopposed.

Today, Fort McAllister has a lushness of pristine grass-covered mounds and stately oak trees thanks primarily to the philanthropic efforts of Henry Ford, who reclaimed and restored the fort solely for the sake of posterity. The barren waste and blight that was once Fort McAllister’s mantle, now lives only amongst old photographs alongside faded handwritten letters in cursive, penned by soldiers and their kin on both sides of the Civil War, each silently looking out at us from the blue and grey folds of the not-so-distant past.